In November 1778, a British corps under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell sailed from New York to Georgia. The troops included around 900 men belonging to the two Hessian regiments Trümbach (originally von Rall, then successively called von Wöllwarth, von Trümbach, and d’Angelleli) and Wissenbach (after 1780 called Knoblauch), both under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich von Porbeck. (Here is a soldier’s artistic rendering of the fleet Sailing to Savannah, Georgia, 1778).

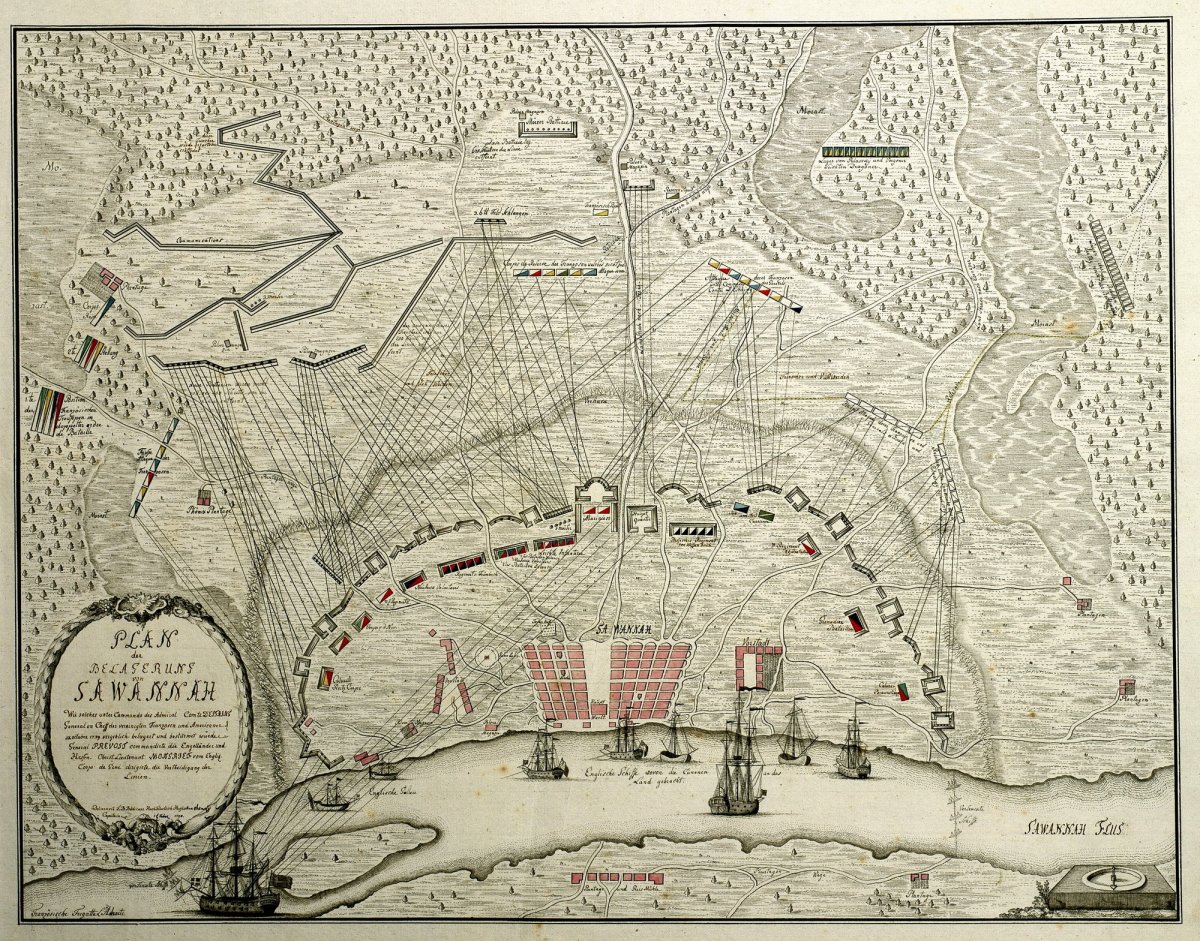

Within days of their arrival at Tybee Island, Georgia, in December 1778, they took control of Savannah. Ten months later, in September and October 1779, the troops successfully defended the city from a French-American siege and attack. The British were ecstatic. General Clinton thought that the victory was “the greatest event that has happened the whole war” (William B. Willcox, ed., The American Rebellion: Sir Henry Clinton’s Narrative of his Campaign, 1775-1782 (Hamden, CT, 1971; orig. publ. 1954), 149n1). It was a proud moment for the Hessians that took part in this battle. The Southern campaign was off to a good start.

Most of the troops would eventually be sent to South Carolina. However, the Knoblauch Regiment remained in Savannah until the British evacuated the post in July 1782. Based on Porbeck’s surviving accounts, the troops must have been miserable. The entire lowcountry was deemed extremely unhealthy, but Georgia, Porbeck claimed, was known as the deadliest province for Europeans in all of North America. Much of the province was covered in dense woods and marshland, and, according to German accounts, populated by snakes, crocodiles, tigers, wolves, bears, and other wild animals. Savannah’s roads were covered in fine sand one foot deep; walking on them felt like walking in deep snow. The city and surrounding countryside were constantly enveloped by a thick fog that gave the region a bad smell. The water was foul and the climate unbearable. The locals were hostile. Everything was expensive and fresh provisions scarce. Under the circumstances, it is not surprising that the number of desertions steadily increased over time. This was especially the case after the British defeat at Yorktown in the fall of 1781, and again after February 1782, when Georgia’s newly elected rebel governor John Martin published a German-language proclamation that promised each German non-commissioned officer or soldier who ran away from the British army a gift of 200 acres of land, a dairy cow, and two brood swine.

However, the regiment’s greatest challenge by far was disease. The regiment had many sick year round, but summers were especially bad. Porbeck himself contracted Yellow Fever at one point. There were times when the regiment had no more than sixty men who were fit for service.

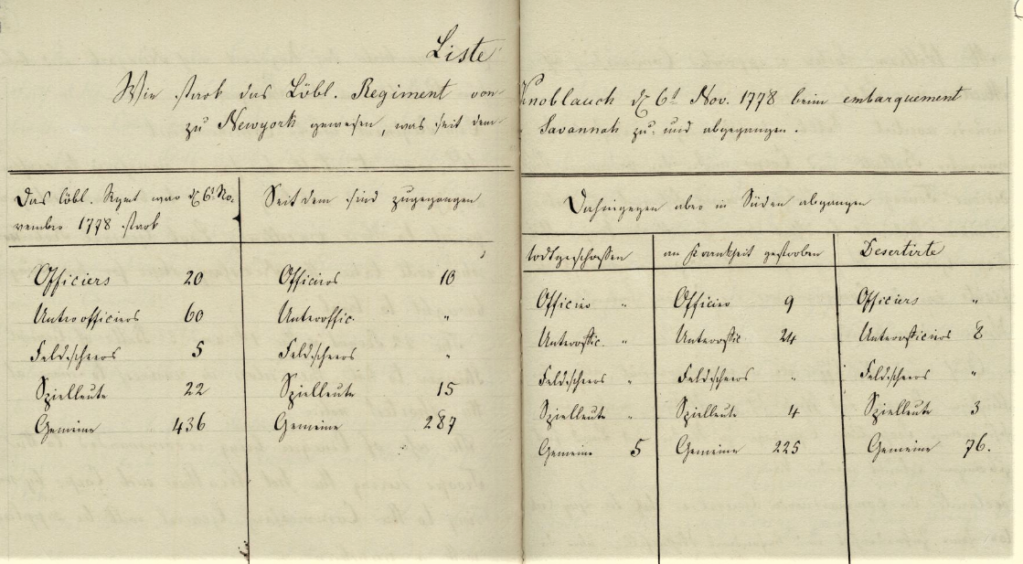

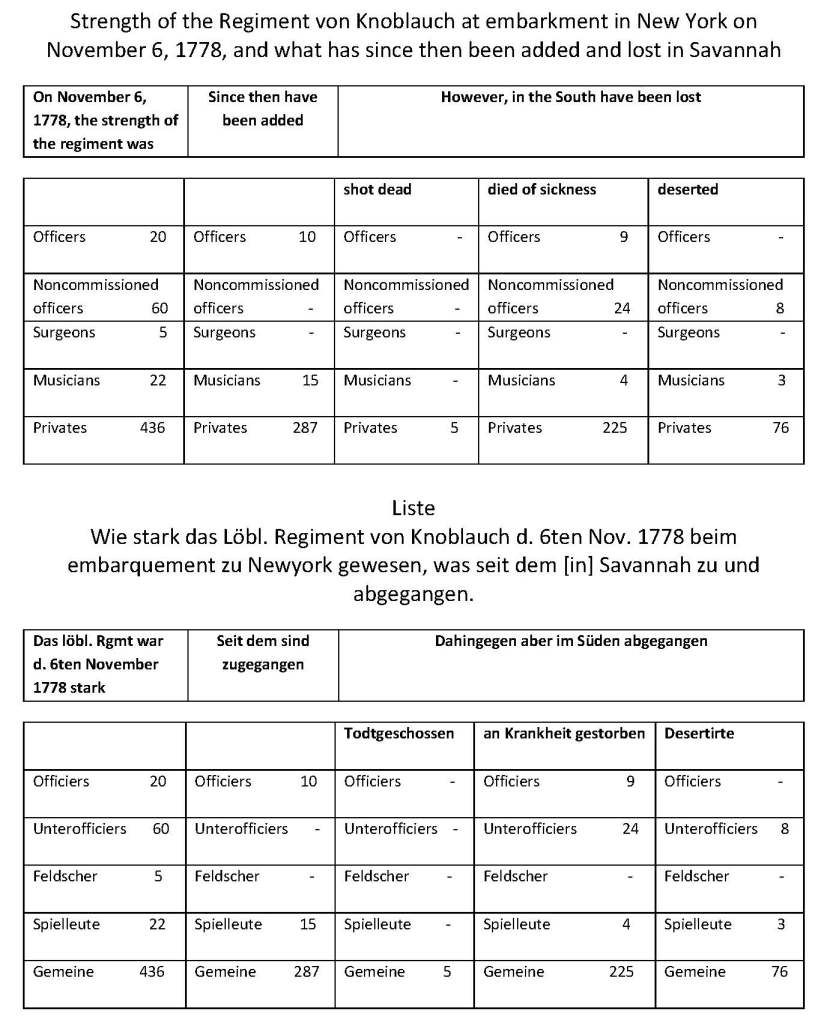

The document included with this post comes from the regimental journal of the Knoblauch regiment. Although it is not dated, it is evident that it covers the period from the regiment’s departure in New York in November 1778 to the evacuation of Savannah in the summer of 1782. Even without counting the losses among servants, laborers, women, and children, which were not recorded, around one third of the regiment did not survive its time in the South. Disease killed almost all of them.

According to the list, a total of 855 soldiers belonging to the Knoblauch Regiment went to Georgia between November 1778 and July 1782. Of those, 354, or about 42%, were lost. Five were shot dead, 262 died of disease, and 87 deserted.

Citation: Tagebuch des Garnisonsregiments von Knoblauch, August 1782, ff. 300-301, 4° Ms. Hass. 205, Universitätsbibliothek Kassel, Landesbibliothek und Murhardsche Bibliothek der Stadt Kassel.

Some of Porbeck’s records are included in “Angelegenheiten des in Amerika stehenden hessischen Garnisonsregiment v. Wissenbach, später v. Knoblauch bzw. Koehler, 1764-1768, 1777-1783,” HStAM, Fonds 4h, Nr. 3139, Hessian State Archives Marburg.

Image: F. B. Bödicker, Plan der Belagerung von Savannah wie solches unter Kommando des Admirals Comte Destains, General en Cheff der vereinigten Franzosen und Americanern den 9. Oktober 1779 vergeblich belagert und bestürmet wurde, 1779, HStAM WHK 29/77b, Hessian State Archives Marburg.

One thought on “Shot Dead, Died of Disease, Deserted. Savannah, 1778 to 1782”