On occasion, German-authored correspondence and diaries include poems. Some of them memorialized events or experiences directly related to the war. This post features a song, or poem, by an unknown author that commemorated the unsuccessful French-American joint attack on British-held Rhode Island in August 1778. It is included in the diary of Captain Friedrich Wilhelm von der Malsburg (1745-1825) of the Hessian Regiment von Ditfurth. Malsburg participated in the Battle of Rhode Island (he was slightly wounded and his dog was shot dead). The poem depicts both the French and the Americans as stupid and cowardly. It is a satirical piece that reflects the Germans’ confidence in the superiority of the British army over the enemy.

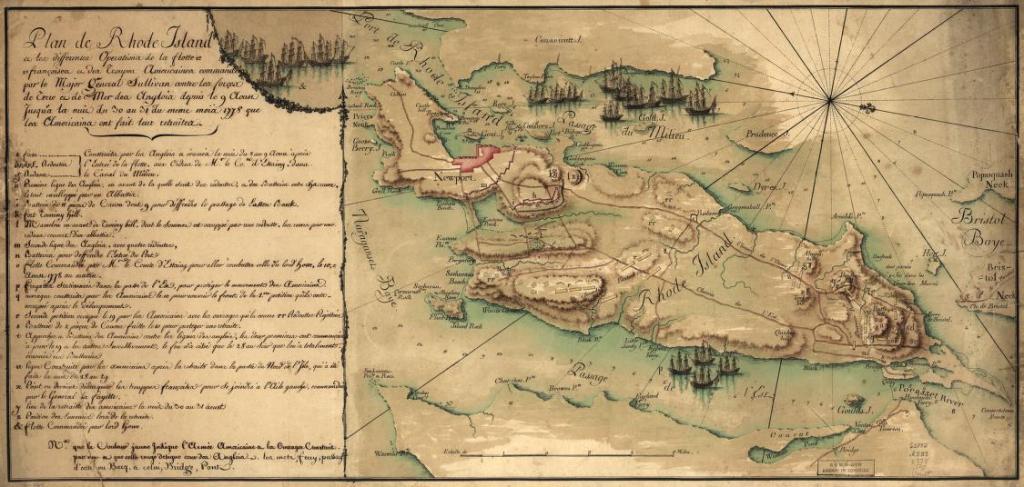

In December 1776, a fleet carrying as many as 7,000 troops under the command of General Henry Clinton (1730-1795) arrived in Rhode Island. Within days of dropping anchor in Narragansett Bay, they occupied Newport and the surrounding countryside on Aquidneck Island (Rhode Island at the time). A few days later they also took Jamestown (Conanicut Island).

Clinton’s troops were made up of roughly equal parts of British and Germans. The latter belonged to several Hessen-Kassel regiments (Prinz Carl, Leib, Landgraf (until March 1777 Wutginau), von Huyn, von Bünau, von Ditfurth), under the command of General Friedrich Wilhelm von Lossberg (1720-1800). The Prinz Carl and Leib regiments returned to New York in May 1777; they participated in General Howe’s expedition to Philadelphia. The two Ansbach-Bayreuth regiments were sent from New York to Rhode Island in the summer of 1778. Along with the four remaining Hessian units, they remained there until 1779. The commander of the British in Rhode Island was Major General Robert Pigot (1720-1796).

In April 1778, a French fleet under the general and admiral Jean Baptiste Charles Henri Hector, Comte d’Estaing (1729-1794), sailed from France in order to provide assistance to the Americans. When it became clear that the Americans and French had selected Newport as the target of their first allied expedition, the British immediately dispatched around 2,000 troops from New York to Rhode Island as reinforcements.

In late July, the French fleet sailed into Narragansett Bay. In addition to utilizing land forces, the French were to attack from the sea while the Americans, which were commanded by Major General John Sullivan (1740-1795), launched attacks on British and German posts from the interior. The fighting commenced in early August. Within days, relief arrived in the form of a large British fleet under Admiral Richard Howe (1726-1799). The French and British fleets prepared for what could have been the most significant naval battle of the war. However, a massive storm left the fleets scattered and damaged, and both sailed off.

By the end of the month, the Americans began to withdraw to the north of Aquidneck Island. In an attempt to prevent their escape across the water to the mainland, the British pursued them. On August 29, the fighting culminated in a general engagement, known as the Battle of Rhode Island. The following day, General Sullivan managed to remove the last of his troops from the island, leaving it under British control. The first attempt at French-American military cooperation had failed.

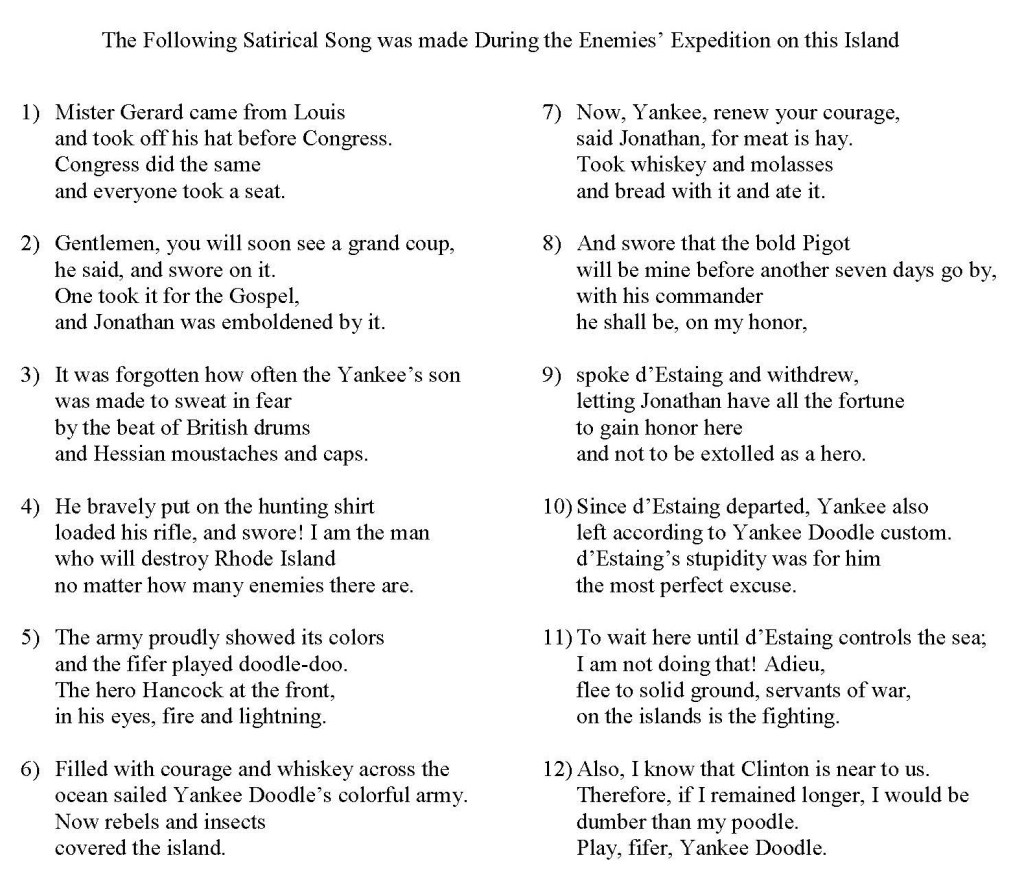

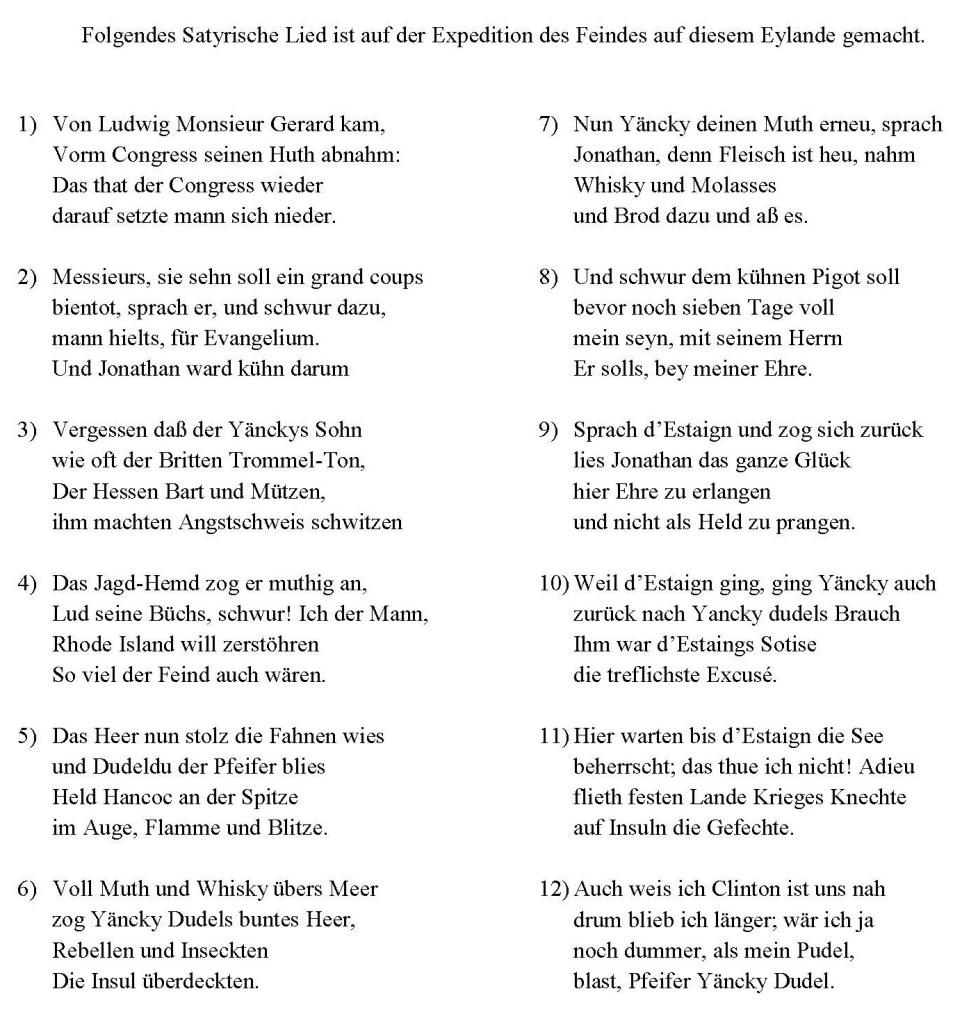

The poem that Captain Friedrich Wilhelm von der Malsburg copied in his diary ridicules the French decision to become American allies. In addition, it makes fun of the Americans – the “Yänckys” – as being determined but ultimately cowardly. Without French assistance, they quickly gave up and took off. Of course, in reality, the troops under General Sullivan put up fierce resistance and inflicted serious damage over the course of several weeks in the summer of 1778. The main feature of their strategy seemed to have been firing at the enemy from concealed positions, such as walls and hedges. It is no coincidence that the poem identifies the American, or Yankee, as a rifleman.

In addition to d’Estaing (spelled d’Estaign in the poem), Pigot and Clinton, the poem includes references to the following individuals:

Ludwig refers to the French king Louis XVI (1754-1793). He had assumed the throne in 1774. Gerard refers to Conrad-Alexandre Gérard de Rayneval (1729-1790). Rayneval participated in the American-French negotiations that resulted in the Treaty of Alliance. He was the first French Minister to the United States, and he sailed to America with d’Estaing in the spring of 1778. Jonathan, or Brother Jonathan, was a commonly used personification of New England. Hancoc refers to John Hancock. In the summer of 1778, he was a delegate from Massachusetts in the Continental Congress.

The German version has stanzas with two rhyming couplets each (AABB). I did not attempt to mimic this scheme in the English translation.

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

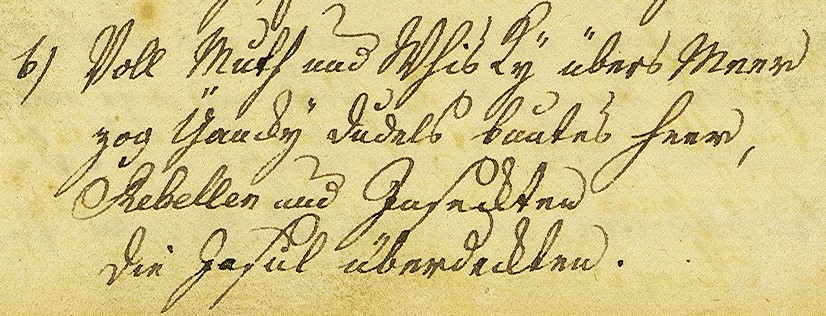

TRANSCRIPTION

Citation: [Friedrich v. d. Malsburg], “Tagebuch eines hessen-kasselschen Offiziers aus der Zeit seiner Teilnahme am Krieg gegen die Vereinigten Staaten von Nordamerika,“ ZSt Curiosa Nr. 65, f.65 (October 1778), Austrian State Archives, War Archives Department (Kriegsarchiv).

Featured Image: F. Audibert, Plan des Lagers von Rhode-Island und der unter dem Kommando des Generalmajors Presgott darauf befindlichen Campements, 1781, HStAM WHK 29/68, Hessian State Archives Marburg.

Interested in any activity by Regiment Prinz Carl and knowing that the regiment was in Newport, I looked at all of the information here. Hard to find anything beyond the names of a few officers, other regiments, and “hessians”. Regiment Prinz Carl was only there for about 6 months.

The Germans were very new to America at this point so their attitude towards Americans was strongly influenced by the British and their first few encounters with the rebels.

Interesting to see the German of that time. The German language has changed a lot in my lifetime. Compare German of the 1960s with today’s.

I’m in a bit of a conundrum as an American with both German and British ancestry.

Here in 1624 on my British (Scottish) side and 1875-85 on my German side. I wish German troops had not come, am glad that the musketeers in Regiment Prinz Carl did not see much combat, the grenadiers saw far more as members of the combined grenadier battalion von Block, Lengerke. Disease was a major cause of death.

On the other hand, having Germans from towns my family lived in long ago has been a very interesting story and helped me learn not only about them, but about the conditions in Germany in the late 18th century.

54mm Zinnfiguren of the Regiment Prinz Carl have resulted from the reawakening

of my Hessian ancestry interest as a result of this book.

LikeLike