If one wanted to pick the worst month for the German auxiliary troops in North America, it would likely be October 1777. That month, contingents belonging to the German corps suffered two devastating defeats.

The first took place on October 17. That day, the British army under General John Burgoyne formally surrendered to the American army under General Horatio Gates at Saratoga, New York. As a result, around 1,800 Braunschweigers and 600 troops from Hessen-Hanau (plus a number of women and children) entered captivity. The defeat was the culmination of a long campaign that included the Battles of Bennington (August 16), First Battle of Saratoga (Freeman’s Farm, September 19), and Second Battle of Saratoga (Bemis Heights, October 7), all of which resulted in significant losses for the German corps. Moreover, the surrender at Saratoga helped convince France that the Americans could win the war against Britain. France’s financial and military support of the rebellious colonies was formalized with the Treaty of Alliance four months later. The entry of France into the war on the American side is the main reason why the Battle of Saratoga is often called the turning point of the Revolutionary War.

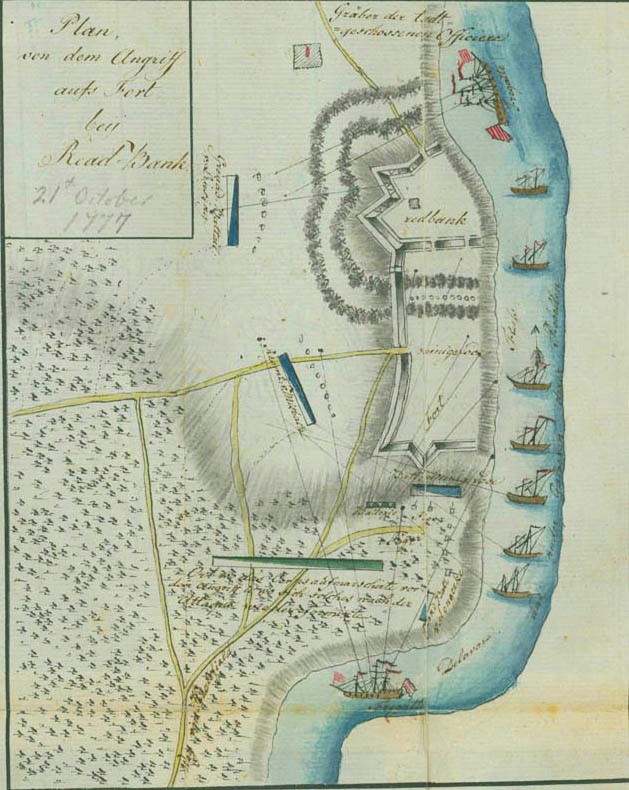

The second defeat took place less than one week later, on October 22.

In July 1777, more than 15,000 British and German troops along with officers, staff and servants, had boarded transports at Staten Island that would take them to Philadelphia. In August, the fleet landed in Maryland, and from there the army made its way north toward Philadelphia. On September 26, they marched into the city. However, several weeks into the occupation of Philadelphia, the Americans were still holding two strategic posts on the Delaware River that prevented British supply ships from reaching the city. One of them was Fort Mifflin on Mud Island in the middle of the river, and another was Fort Mercer (known to the Germans as Fort Red Bank), across the Delaware on the New Jersey side south of Philadelphia. Until the British gained control over these posts, they would not be able to bring in much needed supplies and provisions.

In mid-October, the British made preparation for an attack on Red Bank. At that time, Mud Island was already being bombarded by batteries located on Province Island near Philadelphia, but with little success. The detachment selected for the attack on Red Bank was comprised almost entirely of Germans, including Hessian units and Hessian and Ansbach Jäger. The force of 2,000 men was commanded by Colonel Carl Emil Ulrich von Donop. Red Bank was occupied by just under 500 Americans under the command of Colonel Christopher Greene.

On October 22, Donop’s force attacked. According to the Hessian Jäger Johann Ewald, the troops marched “against the fort with indescribable courage” (Diary of the American War: A Hessian Journal, ed. Joseph P. Tustin [New Haven, CT, 1979], p. 99). It turned out that they walked right into a relentless barrage of fire from the fort and from several rebel ships. British warships were unable to get close enough to be of any help. Within minutes, dozens of Hessians were killed or wounded. The heavy losses forced the corps to retreat. In all, they suffered more than 400 casualties. Donop was one them; he was mortally wounded and left behind. Red Bank would be the costliest American battle for the Hessians in terms of their number of dead and wounded.

There was general agreement among the German officers that the attack on Red Bank had been a major mistake. Among the German officers who shared their thoughts on the matter was the Hessian officer von Wurmb. In a letter addressed to his friend Friedrich Christian Arnold, Baron von Jungkenn, in Kassel, Wurmb pointed to Donop’s inability to get along with his superiors as the main reason why the expedition had been executed, even though it was generally believed that the fort could not be taken. When Donop demanded permission to storm it with his brigade, General Howe readily agreed, presumably based on the assumption that it would humble the Hessian officer. Wurmb believed that Howe did not think that Donop would actually go through with the attack. But he did, with devastating consequences.

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

[Excerpt from letter dated February 7, 1778]

The unfortunate affair with Donop probably caused some alarm in Kassel. Indeed, it is the brave men that were shot dead or became disabled that are to be lamented. Based on my limited insights, the entire thing should not have happened, as the outcome has indeed shown. As soon as we took Mud Island (“Mott Eyland”), Red Bank (“rotbänks”) was abandoned on its own. Based on what I have heard under the hand, I think that the late Donop is to blame for this. You know him, dear General Jungkenn, and that he never got along with anybody who was above him. He had made General Howe and all of the English generals to enemies with his salacious letters and open feuding. Among other things, he said publicly that General Howe conducted one march as a general. The others would have been done better by an ensign. Of course, General Howe was very offended by this. When the siege of Mud Island was undertaken, Donop said publicly that this was approached incorrectly, and that one had to take Red Bank first. He wished that General Howe would give him permission to do this with his brigade. It is said that he personally asked the general for it. He received it [permission], and I suspect that General Howe did not think he would do it since it [the fort] was impossible to take, and that he intended to ridicule Donop. Donop noticed this, and because he did not want to expose himself to this [ridicule], he dared it and struck out badly. This is my opinion that I have of this matter. Had Donop remained alive, he would have gone to Kassel this year; General Howe would not have kept him here.

TRANSCRIPTION

[Auszug aus einem Brief vom 7. Februar 1778]

Die Unglückliche Affere mit den Donop wird in Cassel etwas allarm gemacht haben, und es sind in der thatt die praven Leute welche tot und zu Krüppeln geschossen sind zu beklagen, nach meiner wenigen Einsicht hätte diese gantze Sache unter bleiben können, wie es dass Ende auch gezeigt, Wie wier Mott Eyland [Mud Island] hatten, sind die rotbänks [Red Bank] von selbsten verlaßen, ich glaube, waß ich unter der Hand gehört habe, daß der verstorbene Donop daran schuld gewesen ist, Du kennst ihm lieber Genl. Juncken, daß er sich niemahlen mit den seinigen vertragen konte die mehr wahren wie er. Er hatte sich den G[enera]l. Howe und alle Englische Generals zu Feinden gemacht, durch seine Anzügliche Brieffe, und freues zehden unter anderem hat er öffentlich gesagt, daß der G[enera]l. Howe auf der lezden expeticion, einen Marsch als general gemacht hätte. Die übrigen müste ein fänderich besser machen, und dieses nahm der G[enera]l. Howe wie natürlich sehr übel, als nun hier die Belagerung von MottEyland unternommen wurde, so sagede Donop öffentlich daß dieses unrecht angefangen wehre, man müste erst die rothbanks wegnehmen, er wünschde daß Ihm der G[enera]l Howe die Erlaubniß gebe solches mit seiner Brigade zudhun, und wie man sagt, so hat er auch personellement bei den G[enera]l darum gebehden, Er bekam selbige, und ich vermuthe daß der G[enera]l Howe geglaubt hat, daß er es nicht unternehmen würde, weillen es nicht zu nehmen wahr, um den Donop dadurch lächerlich zu machen. Donop der dieses merkte, und sich diesem nicht auß setzen wolte, wagede es, und schlug so unglücklich auß. Diese ist meine Meinung welche ich von dieser Sache habe. Wen Donop wehre leben geblieben, so wehre er doch diese Jahr nach Cassel gekommen, der G[enera]l Howe hätte ihm nicht hier behalten.

Citation: Wurmb to [von Jungkenn], Feb 7, 1778, Jungkenn Papers, Correspondence and Documents, Box 1, Folder 63, Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Featured Image: [Detail] “Red Banke,” [1777?], Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library.

NOTE: In the summer of 2022, an archeological dig just outside Red Bank Battlefield Park uncovered the skeletal remains of at least a dozen individuals, all of whom are believed to have been Hessian soldiers who lost their lives in the battle. For more information, go here.

The information provided in this post combined with information about events that took place on the day of the battle ensured the results. Intelligence about Fort Red Bank, aka Fort Mercer, was incorrect by the time of the attack.

More artillery was available to the Americans.

The fort was made smaller, easier to defend.

Hessian soldiers who made it inside an outer wall, were then trapped by this wall. They were easy targets for American artillery.

The planned route to Fort Red Bank had to be changed, the Hessians marched two times further than planned before the attack. This delayed the attack to late afternoon.

Hessian artillery was insufficient. It could not be elevated to reach targets in the fort and was not the caliber needed to attack a fort.

American ships were able to target the Hessians as they attempted to reach the fort.

Like the Battle of Bennington, the Germans were sent on their own, had little or no English language capable personnel. This made success less likely.

Evacuation after the battle was difficult, it was pretty much every man for himself. Many wounded were left behind, Von Donop and others were buried at the site.

Yes, this period between the Battle of Bennington, Saratoga, and Red Bank was the worst for German troops. The results certainly didn’t help the British either.

One comment I’ve read said the German troops only prolonged the war. The outcome was inevitable.

I’m still quite excited about this book. Having an author fluent in German and English and access to German archives makes a huge difference. Thank you, Professor Baer.

Robert Moeller

LikeLike