The two documents included with this post are letters written in English by two men belonging to the corps from Braunschweig. The authors are Chaplain Johann August Leonhard Kohle (?-?) of the Regiment Specht, and General Staff Auditor Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Zincken (1729-1806). (Note that his name appears as Zencken and Zincken in his letter). They belonged to the Convention Army, the name used to describe the more than 5,000 British and German soldiers that entered captivity as a result of General Burgoyne’s surrender at Saratoga, New York, in October 1777. Within days of the surrender, the prisoners were marched to Boston, Massachusetts. The German troops were quartered in barracks on Winter Hill while most of the officers lodged in Cambridge and surrounding towns outside of Boston. Six months later, in May 1778, more than 2,000 German captives were still there, including Kohle (at Winter Hill) and Zincken (in Cambridge). The American officer in charge of managing the Convention Army during their stay in Massachusetts was Major General William Heath (1737-1814), commander of the Eastern Military District. His headquarters were in Boston.

The two letters date to May 1778 and are addressed to Heath. Although written on different dates and independent of each other, they had the same purpose: Kohle and Zincken were eager to visit Boston, and they hoped that Heath would grant them permission to do so. Kohle explained that the proper execution of his duties as a “Lutherian” chaplain required the use of wafers for religious services which he hoped to acquire in Boston. In addition, he wished to visit several well-known printers in order to peruse or perhaps purchase some books. He not only described himself as a great admirer of the “solide” sciences but also claimed that he had a “multitude” of esteemed friends in Boston, including even the president of Harvard College. Zincken, who asked to go to Boston with his servant, described it as “a Town which is the first and principal of the hole america.” He wanted to visit it so that he could judge for himself. Also, he claimed that he had a few cousins there whom he wanted to see.

In addition to serving as evidence for the Germans’ curiosity about their surroundings, including cities like Boston, the two letters also point to a major challenge faced by members of the German corps serving in North America: the language barrier. A handful of German officers had studied English or may have picked up some English language skills during previous service in the British military. Some forward-looking soldiers acquired at least a basic knowledge of the English language during the voyage to America. However, the vast majority of the German soldiers and civilian members of the corps had no knowledge of English when they set out for America, and many struggled to acquire even a basic command after their arrival. Not surprisingly, the degree to which Germans mastered English depended on a number of factors, including the demands of their role within the military, personal interest in acquiring language skills, length of service in America, and opportunities for interactions with English speakers, including Americans.

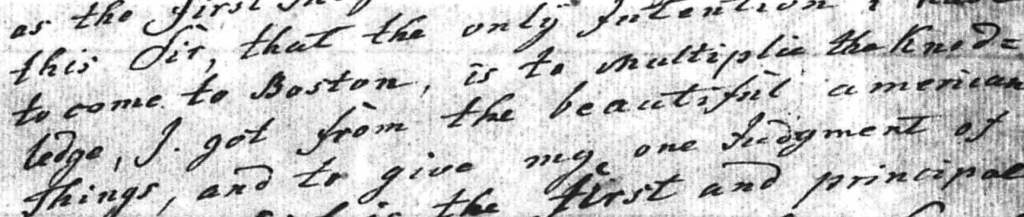

That Zincken and Kohle knew some English after almost two years in North America (including seven months as prisoners of war) is not surprising, especially given their respective roles as chaplain and auditor. However, it is evident from the documents that their language skills remained limited. (I am assuming that they penned the letters themselves.) The meaning of some phrases is unclear. Aside from issues with spelling, readers of German will readily recognize some of the syntax as German. In addition, it was not easy for these writers to compose their letters in the Latin script as opposed to the German style (Kurrentschrift) they normally used. Zincken avoided cursive altogether, opting instead for a printed style.

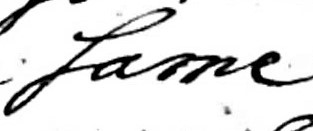

Kohle managed to compose his letter in Latin script; however, a more experienced writer would not have used the long “s” quite as liberally. As an example, here is how Kohle writes the word “same”:

Despite these issues, both writers were able to articulate their requests in English; Heath would certainly have gotten the gist of them. Unfortunately, answers from him are not known to exist. However, it is likely that he responded favorably. After all, the two men were not soldiers or military officers (who were prohibited from entering Boston). Moreover, Kohle’s intention to purchase wafers for religious services and to visit printers in search of “elegant litterature” seemed reasonable and admirable, as did Zincken’s explanation that he wished to “multiplie the knodledge” he “got from the beautiful american Things.” Both also clearly aimed to flatter the American commander.

Note: In order to convey the writers’ styles, spelling, punctuation, and syntax have not been changed or corrected. The transcriptions are faithful to the originals.

TRANSCRIPTION (Kohle letter)

Sir,

Touched from the thanksful Feel of Your Goodness, granted by Mr. Major Hopkins, against me, being a German Chaplain, of which You no yet have [illegible], I take the honour, to declare[?] to You the reasons of necessity, to pray the Concession some times to repaire to Boston. I have diverses Requests, belonging to my Office, and the attainment of them remains to me impossible, without Boston, in the whole verges, assigned to me, to abide in them. We Protestants Christians, Lutherians named, celebrating the Lord Supper, need the sort of very little Bread, Oblates named in our religious Assembly: not only I seek themselves, with hope to find in your Town, but also the machine, to prepare the same. —-

Being a lover of the very elegant litterature, I wish to visite the printed Office of Mr. John Gill, Mr. Greenleaf and perhaps another Printers [illegible] the Fame sure, to being to Boston Richesses of much good and learnedly wroten Books, I desire to have notice of them, and some in possession: I have the men of soldides sciences in the greatest esteem; and their Friendship is my Fortune. The first in a multitude of them, dwelling to Boston, is the most honourable President of the College of Cambridge. All this purposes, affording to me the very great Use, I wish to procure, because to have nourishment for my Spirit, during my present lodgment upon Winter Hill. I have the confidence in Your Generosity, that you will condescendent to my desire and Petition. In my affairs, before mentioned, is not the least, Sir, what I shall say in the first place to you, being present before you, viz that I persevere

Sir,

Your most obedient, and humble Servant John August Lionhard Kohle, Chaplain of the Regiment of Infanterie of the Brigadeer Specht from the Bronswiks Troops.

From the Winter Hill, the 18th May, A.D. 1778

TRANSCRIPTION (Zincken letter)

To the honorable Major General Heath

Sir!

Pray to excuse to have the Permission I and my Servant to come to Boston, for to Seen the Twon, and several things therein, from wich it’s made such a great mention.

I am what is said by you, a [Suitor?] of the Justice, and employed by the Bronsvic Troops as the first Judge advocate. You’ll know by this Sir, that the only Intention i have to come to Boston, is to multiplie the knodledge, I got from the beautiful american Things, and to give my one Judgment of a Town which is the first and principal of the hole america, and i have several coussins in this Town, with i wich to seen.

I am with the greatest Respect

Sir

Your most obedient Servent Charle Frederic William Zencken

by Master Munsfild Taply [Mansfield Tapley?]

Cambridge, the 24 Mai 1778

Citation: Both documents are in the William Heath papers (1774-1872), accessed on microfilm at the American Philosophical Society, call# Mss.DLAR.Film.62 reel 9.

Featured Image: Franz Xaver Habermann, Vuë de Boston. Prospect der König Strasse gegen das Land Thor zu Boston / Vuë de la Rue du Roi vers la Porte de la Campagne a Boston (1778), Library of Congress.

One thought on “The Beautiful American Things. Boston, 1778.”

Comments are closed.