In June 1778, the British decided to abandon their hold on Philadelphia and withdraw the troops stationed there to New York. A few weeks before their departure, General Henry Clinton had replaced William Howe as the commander-in-chief of the British forces in North America. The year 1778 would bring a new campaign under a new leader into a different part of North America.

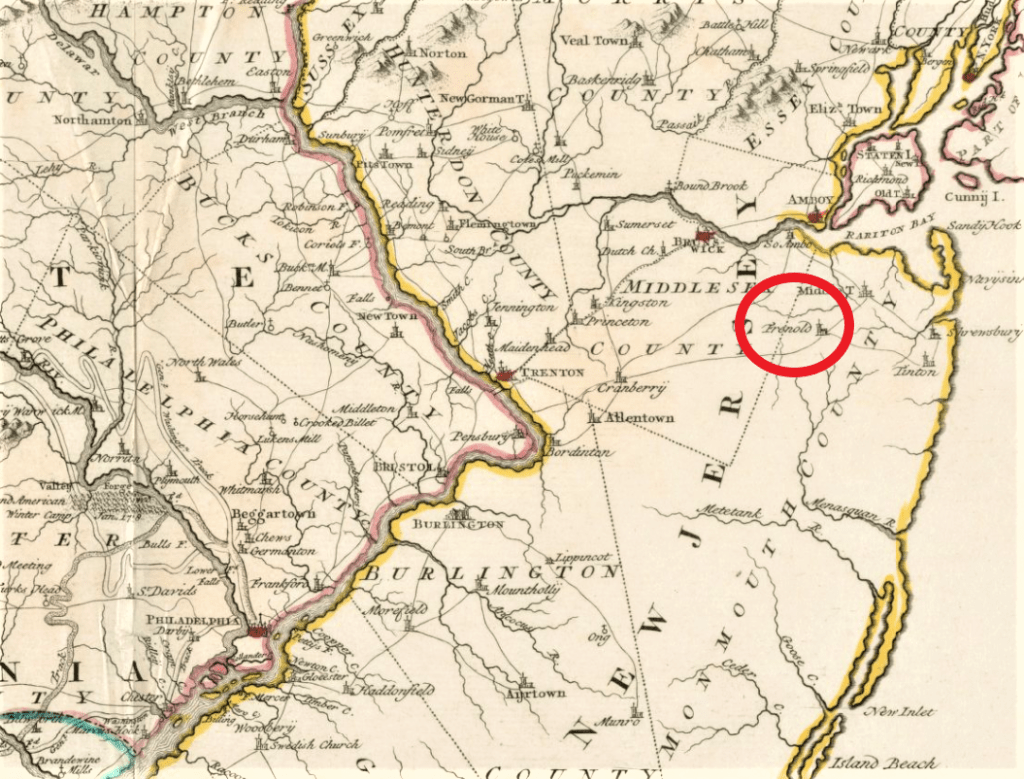

It turned out that the troops’ return to New York was far more arduous, and costly, than anticipated. The army consisted of more than 20,000 people, including thousands of Loyalists, women, children, and other civilians. Slowly, the train of people and baggage — more than ten miles long — made the 100-mile trek to New York. They marched in two divisions, one commanded by Lord Cornwallis and the other by Wilhelm von Knyphausen, the commander of the Hessian forces in America. It was one of the most exhausting marches the Germans had experienced since arriving in America. The extreme heat was almost unbearable. On some days, the temperature exceeded 100 degrees Fahrenheit (c. 38 degrees Celsius). Torrential downpours offered no relief; in fact, the high humidity worsened conditions. The Americans, moreover, did their best to make the march as challenging as possible. They destroyed bridges and blocked roads, and they continually harassed the troops.

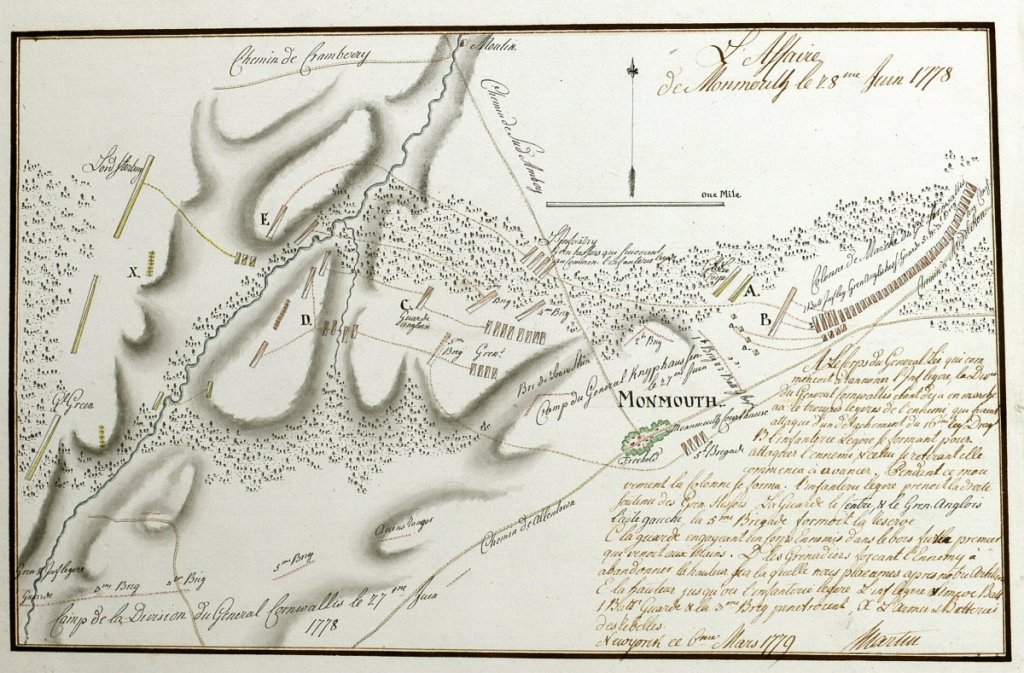

More significantly, in late June, the Americans attacked the army near Monmouth Courthouse. Clinton struck back with force, and the two sides battled until darkness forced them to quit. Multiple accounts by soldiers on both sides include complaints about the stifling heat that day. More than one hundred Americans, British, and Hessians reportedly died of heatstroke during the battle. The total number of dead and wounded may have exceeded one thousand (Mark Edward Lender and Garry Wheeler Stone, Fatal Sunday: George Washington, the Monmouth Campaign, and the Politics of Battle [Norman, OK, 2016], 366-368). The following day, Washington discovered that the British had resumed their march toward New York. Two days later, the army with its large quantity of valuable baggage arrived safely at Sandy Hook.

Washington presented it as an American victory. On the second anniversary of American Independence, he was in good spirits. It “had turned out to be a glorious and happy day.” “Without exagerating,” he wrote to his brother John Augustine, “there [sic] trip through the Jerseys in killed, Wounded, Prisoners, & deserters, has cost them at least 2000 Men & of their best Troops” (George Washington to John Augustine Washington, July 4, 1778, Founders Online, National Archives).

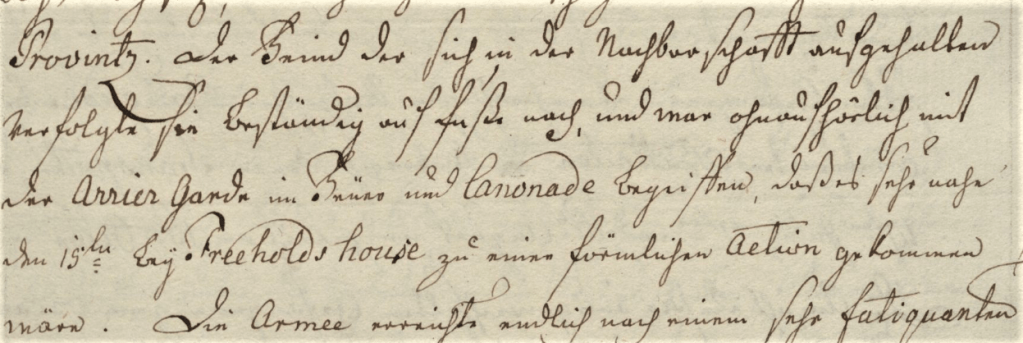

Among the Hessian units that marched from Philadelphia to New York in the summer of 1778 was the Grenadier Regiment von Bischhausen. The relatively brief entry in the regimental journal focuses on the constant harassment by the enemy. Around June 15 near “Freeholds house,” the entry notes, the fighting became so heated that it almost amounted to a “formal action.” It is possible that the scribe, Major Johann Wilhelm Endemann, got the date wrong and he was actually referring to the Battle of Monmouth which took place around two weeks later. He does not mention another skirmish or battle. The entry does, however, explain that the excessive heat took a significant toll on the troops. A number of men died. Others, too weak to keep up, were captured by the enemy. The journal mentions that there were deserters but does not offer an estimate of how many troops may have run away. Other sources suggest that the number of Hessian deserters may have been around 236. Knyphausen believed that the men had been induced to take this step by American offers of property and by the glowing accounts of life in Pennsylvania shared by German soldiers that had been released from captivity (Rodney Atwood, The Hessians: Mercenaries from Hessen-Kassel in the American Revolution [New York, 1980], 193-194). One Hessian officer estimated that the army as a whole lost more than 800 men to desertion, battle, or fatigue (Friedrich Wilhelm von Wurmb to von Juncken [sic], [July 1778], William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Freiherr von Jungkenn Papers, Correspondence and Documents, Box 2, folder 11).

Although Clinton had managed to bring the army back to New York (and Washington’s numbers of estimated enemy losses were exaggerated), the “trip through the Jerseys” had indeed been costly.

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

[June 1778]

In the meantime, it became very clear that we would not be safe for much longer from a visit by the French fleet. And since Philadelphia was not the place where an army could defend itself for long without having access to the open sea, the commanding general had no choice but to evacuate the city. Accordingly, after the frigates, transports and provision ships on the Delaware had departed for New York, this was accomplished successfully on June 9. The entire army was taken across the Delaware to [New] Jersey in boats, from where it continued the march through this province. The enemy, who had been in the vicinity, chased us the entire time on foot. They were continuously engaged with the rear guard in firing and cannonading, so that it almost came to a formal action on the 15th near Freeholds House. After a very exhausting march with baggage, sick, and wounded, the army finally reached the area around Sandy Hook. By boat, a portion was taken to Staten Island, a portion to Long Island, and a portion to York Island, where they encamped.

Because of the excessive summer heat during the march through [New] Jersey, many men were left dead on the roads, and others, who were unable to keep up, were collected by the enemy, and some were taken as prisoners and some as deserters.

TRANSCRIPTION

[June 1778]

Inzwischen wusste man gar zu wohl, dass man nicht gar zu lange mehr vor dem Besuch einer französischen Kriegsflotte sicher seyn würde; und da Philadelphia der Ort nicht war, wo sich eine Armee ohne die See offen zu haben, lange halten konnte; so blieb vor den commandierenden General en Cheff nichts [14] übrig, als die Stadt zu evacuieren. Dieses wude demnach auch den 9ten Juny, nachdem vorher in dem Deleware gelegene Fregatten, Transport- und Provisions Schiffe in See und nach New Yorck waren abgegangen, würcklich werckstellig gemacht. Die gantze Armee wurde in Boats über den Deleware auf die Jersey übergesetzt, und nahm ihren Marsch zu lande durch diese Provintz. Der Feind der sich in der Nachbarschaft aufgehalten verfolgte sie beständig auf fusse nach, und war ohnaufhörlich mit der Arrier Garde in Feuer und Canonade begriffen, dass es sehr nahe den 15te bey Freeholds house zu einer förmlichen Action gekommen wäre. Die Armee erreichte endlich nach einem sehr fatiquanten Marsch mit Baggage, Kranken und Blessierten die Gegend von Sandy Hook, wo sie mit Boats, theils nach Staaten = theils nach Long = theils nach Yorck Eyland gebracht wurde und alda campieren muste.

Wegen der excessiven Sommerhitze während des Marsches durch die Jersey sind viele Leute todt auf den Wegen liegen blieben und andere die nicht mitkommen konnten, wurden von den Feinden aufgesammelt und theils als Gefangen, theils als Deserteurs zurückgebracht.

Citation: Tagebuch des Grenadierregiments von Bischhausen, Universitätsbibliothek Kassel, Landesbibliothek und Murhardsche Bibliothek der Stadt Kassel, 4° Ms. Hass. 168, ff. 14-16.

Image: H. Klockhoff, Carte particuliere des environs de Philadelphie (1780), Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library.

In every situation where German troops were came in contact with American forces I wonder how communication was accomplished. In some areas there were German speaking people, but in others few if any. I wonder if French may have been used. Even von Steuben used French to communicate with Washington’s staff at Valley Forge.

With ancestry from today’s Bad Hersfeld-Rotenberg district I am most interested in the Regiment Prinz Carl and the Garnisonsregiment von Seitz. Are their journals, Tagebuch available?

I very much enjoy these blogs. I can read the German, and where I have problems the English translations are wonderful. I can’t tell you how much I enjoy having someone from Germany with an interest in this topic. Until I learned of you more of my sources were in English.

Can you suggest someone who can read the German script found in church records?

I have church records back to the early 1600s. My family record originates in Unterweisenborn near Schenklengsfeld. My family moved from there to Sorga and then Rotensee before emigrating to the US in 1875 and 1885. I have met Moeller, Möller, relatives in Unterweisenborn and Rotensee. When my family left today’s Hessen was a province of Prussia as a result of the 1866 war between Prussia and Austria.

LikeLike

I am glad you are enjoying my posts! Another one will be published shortly; I have a few in different stages of completion.

The language barrier was a real problem. At the time of the Revolutionary War, French remained the lingua franca of the European elites; however, many members of the military did not have a command of it. Very few German soldiers knew English. The Americans usually had not trouble finding a German speaker who could communicate with German soldiers, including captives. Although English language skills among German soldiers improved over the course of the war, many never became fluent enough to carry on a conversation. Holger Th. Graef (Marburg University) published an essay about English-language skills among Hessian officers in North America („Gott daimie und wer weiß wie all das andre heist“ – Zum Unbehagen der hessischen Offiziere im anglophonen Milieu des britischen Militärs in Nordamerika, in Helmut Glück und Mark Häberlein, eds., Militär und Mehrsprachigkeit im neuzeitlichen Europa (Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014) pp. 151–165).

The journal of the Regiment Prinz Carl is in the Landesbibliothek und Murhardsche Bibliothek der Stadt Kassel (shelf mark 2° Ms. Hass. 140). It has been fully digitized (https://orka.bibliothek.uni-kassel.de/viewer/image/1350569133885/1/LOG_0000/). I am not aware of a journal for the Regiment von Seitz. However, it may be worth search other journals because they often include entries that refer to other military units.

For professional transcription/translation services of German records from the 1600s, I suggest reaching out to genealogical organizations for recommendations. I have not used these services.

LikeLike

I’m very appreciate of your efforts and interest. It’s a topic that doesn’t get a lot of attention. It’s very personal for me because of my ancestry.

Your thoughts on communication between German troops and Americans mirror mine. I think it also applies to the British where there was a sense of suspicion, especially as the war continued.

The two battles I have the closest relationship with are Saratoga and Bennington. There are higher ranking officers at Saratoga, possibly more educated, and foreign language capable.

At Bennington, the Americans are mostly country folk. It’s after rather close combat that the German troops are finally captured, brought to the village green and kept under guard.They put up quite a fight. The dragoons fought on foot. Artillery was used. It took help from New Hampshire to prevent the Germans from seizing the stores they sought. Some Germans are buried in the cemetery next to the church on the village green. It was an ill fated mission. Col Baum, the commander, is mortally wounded and dies before reaching Burgoyne’s force. Many believe that the failure to obtain horses and gun powder was a factor in the loss at Saratoga.

I am very grateful for the link to the Tagebuch of Regiment Prinz Carl. I have two challenges: learning how to navigate German internet and reviewing reading German script, but just having the journal is a great joy.

I will reach out to German. genealogist organizations for help understanding the Church records related to my family. Thank you! My Dad and I obtained them in Bad Hersfeld at the church office. I tried to connect with some one here in the US, but was unsuccessful.

It would be interesting to find the music played by the Mohren drummers and the musicians who accompanied them. Even better would be hear that music.

Some years ago, while living in New Jersey, I attended Hessentag at the barracks in Trenton. Reenactors portrayed Hessen-Cassel soldiers. It was a day long event.

I’ve been interested in the “Hessians” since I discovered their presence at Ft Ticonderoga in the 1950s. It has been a slow, now and then, as information became available life long effort. Your work has speeded up the process immeasurably.

I was fortunate to be able to study German in high school, have a pen pal in

Wuerzburg and using information in the family Bible go with him to the town (Rotensee/Hauneck) where my great/grandfather once lived. Once there connections were made. The son of my great-grandfather’s sister was present. It was the house where she lived with him and his twin brother. That was in 1969.

There’s more to my story, but that’s enough for today. So thankful for your help!

LikeLike

I found the full text in modern type and am reading. Very interesting and through the use of the internet I’m able to understand terms in Latin, French words, and old German spellings. Amazing how quickly I came in contact with this document. Thank you very much.

LikeLike