On October 17, 1777, the British army under General John Burgoyne surrendered to the American army commanded by General Horatio Gates at Saratoga in New York. It included approximately 5,800 British and German soldiers who came to be known as the Convention Army. Of these, around 2,400 were German. A large number of them remained in captivity for years.

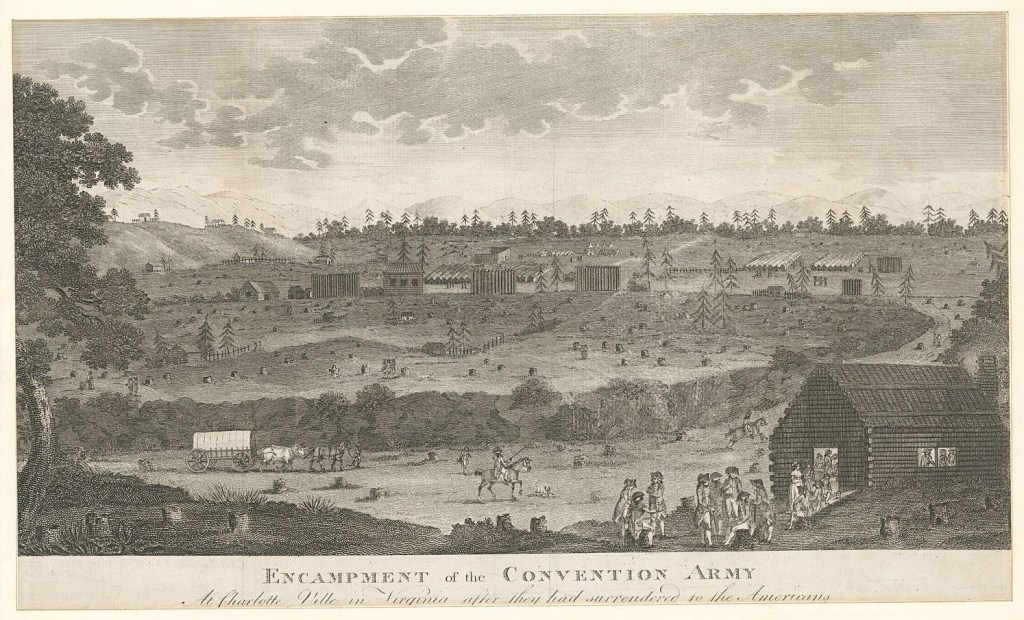

In the winter of 1778/1779, after being held for one year in the Boston area, the Convention Army was forced to march south to Charlottesville, Virginia. Many German observers sharply criticized the Americans for compelling the captives to undertake such a long, difficult journey – around 700 miles – in the midst of winter. It seemed like a needless act of cruelty disguised as necessity. When they arrived in Charlottesville in January 1779, the captives found the “quarters” built for them to be unfinished, with drafty walls and poorly constructed roofs that left them exposed to snow, ice and bitter cold.

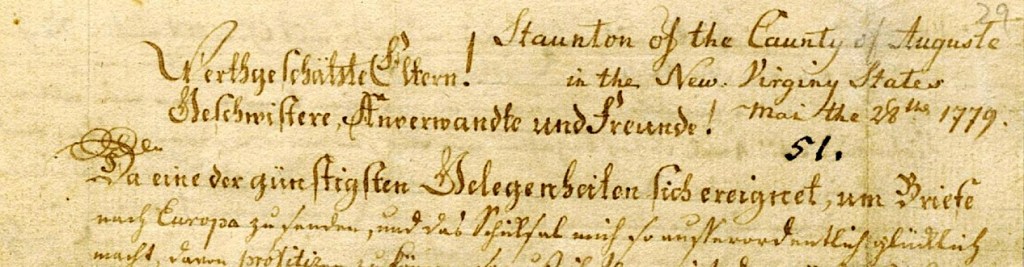

The document featured in this post is a private letter by a member of the Convention Army who experienced these conditions firsthand. It was penned by Johann Christoph Dehn, the Musterschreiber (clerk, record keeper) for the Braunschweig musketeer regiment Specht, which was commanded by Colonel Johann Friedrich Specht (1715–1787). The letter is addressed to Dehn’s parents, siblings, relatives, and friends. Dehn regularly wrote detailed letters to his family and friends back home in Braunschweig (I featured some of his correspondence in another post.)

As a member of the officer staff, Dehn undoubtedly fared better than the thousands of privates belonging to the Convention Army. Yet, his letter indicates that he shared at least some of the hardships during the march south and their time in Virginia, including being housed in half-finished huts during cold, snowy winter months. Dehn describes the dismal living conditions and, perhaps more importantly, a sense of desolation that weighed on the prisoners. He refers to a sense of gloom among an imprisoned force that was “inactive for the King’s service” and in “a boring, disagreeable, and even disadvantageous situation.” He felt fortunate that he was able to leave the crowded, dispiriting barracks after only a few weeks. In early March, he was ordered to Staunton to oversee the delivery of provisions to the officers, a welcome reprieve from the misery of the Charlottesville encampment. He would remain in Virginia for at least one year. By late 1780, he was in New York, most likely on parole.

In the letter, Dehn mentions his friend Heinrich Gerhard, quartermaster for the Regiment Specht. Like Dehn, he was a member of the Convention Army.

To conserve paper, Dehn wrote his letters in a tight script without paragraph breaks. For readability, I have divided the English translation into paragraphs.

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

Staunton in the County of Augusta in Virginia, May 28, 1779

Most treasured parents! Siblings, relatives and friends!

As one of the most favorable opportunities has arisen for sending letters to Europe, and as fate has made me so extraordinarily fortunate to be able to benefit from it, I must tell you with the greatest truth that I am in good health, thank God; indeed, how happy I would be if I could add that I was generally cheerful. But I am not, and you will easily believe me why!

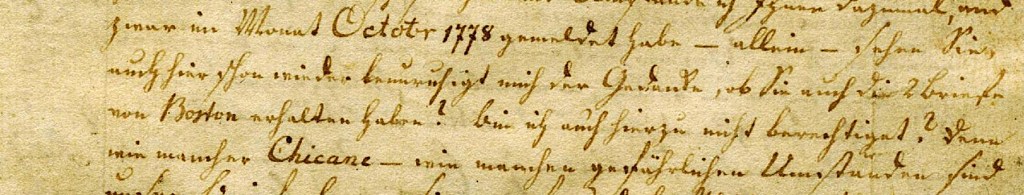

Our fate has not yet improved – a contrary [unfavorable] decision is still keeping us in captivity, which fortunately for us is not as sad, miserable, and especially not as unhappy (as far as the general situation is concerned) as you might think. Although one denies us some of the freedom that we had generally had at Boston, and the nature and circumstances of which I reported to you at that time, namely in the month of October 1778, but, – you see, here I am once again troubled by the thought of whether you have indeed received the two letters from Boston? Am I not entitled to this [worry]? For our letters are subjected to many a chicanery, many dangerous conditions, before they are opened by friendly, compassionate hands. Therefore, my friends, do not expect me to give you an exact description of our march from Boston to Virginia.

You can imagine all the fatigues of a march of 700 to 740 English miles (or 150 German miles) that we had to cover (from November 10, 1778, to January 16, 1779) during such a late season. Imagine our situation and think of all the miserable regions that we traversed, the journey over wide rivers, mountains, deserts and wilderness, and take into account the natural animosity of the inhabitants against us, with which they had to shelter us, by force, in the most awful weather. Add to this the terrible expenses in this country, where we had to pay three to four times as much for all our victuals. Our miserable circumstances with regard to clothing, linens, etc. (for on our arrival in Virginia we had not yet seen anything of our baggage left behind in Canada or of the things sent to us from our fatherland) added to the dreadfulness of our fate.

I am convinced that you will all be and still are very sorry for us, and I must add that you should think of how often we had to camp at night in the woods and wilderness in three to four feet of snow. In a word, think of me as being exposed to all possible hardships of such a march, and would you not expect that even the most resolute courage would frequently yearn for comfort and reassurance? I do not doubt for a moment that you will not tremble for me if you imagine me being exposed to all of these above-mentioned dangers and exhaustion. But thank God that He has bestowed upon me strength and health to endure all these hardships, [and] given me courage, manly courage, to avoid the frequent temptations, and in the midst of tribulation, in the most terrible circumstances, to remember the duties of honor, duties of love, duties of gratitude for my dearest parents and others.

On the 16th of January, we arrived at the place of our destination (7 miles from Charlottesville in the County of Albermarle in Virginia). But here the most dreadful of all awaited us. Nothing of our barracks was finished but the four wooden walls, which were made of logs, between two of which a man could crawl in and out if necessary. An equally miserable wooden roof added to our suffering as the snow was over two feet high in our barracks. No chimney, often no door, and windows were not to be thought of. We had to make a fire in the middle of our barracks [huts] and after two or three days all our rags, and we with them, were smoked. At night, the wind, which was blowing on all sides, and the fierce cold did not let us sleep for a moment, and we were actually in danger of freezing or burning our hands and feet. Another terrible circumstance was that we could not complain to anyone, for each of us had a similar fate. And the Americans said that they had not expected us to arrive as soon as we did, that they had not been able to finish them [the barracks]. Our men, tired from the march, began to build and improve. Now the barracks are in pretty good condition.

I was in them no longer than until March 4, when I was ordered here [to Staunton]. I am therefore fortunate in contrast to so many of my unhappy countrymen that I am 40 English miles from our barracks in a small town, where I receive the provisions for my general as well as for other officers of my corps living here, and must provide an account of them. This assistant commissary position has no other benefit for me than that I have escaped the terrible fate to live in the barracks, which are built in a barren area, and where our whole army is located, and which keeps us imprisoned within the fray of such different people, of equally different principles, and not to be entirely subjected to the misfortune which has hitherto kept us imprisoned as inactive for the King’s service, and ourselves in a boring, disagreeable, and even disadvantageous situation, and for our friends in Europe like the living dead. It also has the benefit for me, on the one hand, that I am at least not completely lulled to sleep and made numb to my own misfortune by the noise and turmoil of my unhappy countrymen, because, on the other hand, the company of various well thinking families here convinces me that all wise prospects have not yet lost sight of me, – indeed, it proves to me that one can certainly be happy even in the midst of misfortune, if one’s own regrets and [other’s] reproaches of evil actions do not embitter this happiness.

This month I have already received 5 letters from you M F. Unfortunately for me, they were from 1776 and 1777. You will understandably be surprised that I did not receive them sooner. They had gone from England to Canada, from where I received them with our baggage, which was left in Canada and has now arrived (namely, the new mounting for our regiment). I have not yet received the two parcels of linen sent to me by H. Krausen in August 1777. One does not know where all these things from our corps have gone. Therefore, pity me, dearest mother, that I still have to do without them in the greatest need. How I wish I could be with you for eight days to tell you many things – very many things – some of which I cannot entrust to my pen, and some of which would be too extensive. Please let Mrs. Gerhard know that her husband [Heinrich Gerhard] is well and that he wrote me a letter yesterday, but that the opportunity to send a letter to Europe has arisen so quickly that I could not inform my friend Gerhard, who is 40 miles away, [in time] so that he could not enclose a letter to his dear wife. Wilhelm is also well. Please recommend me to all those who remember me – Yes! My dearest friends, do not forget your unhappy friend, whose heart sends you longing wishes, and whose eyes, now that the space on the paper commands him to commend himself to you and your friendship, are closing with anxious tears. – Farewell! Farewell! J. C. J. Dehn

TRANSCRIPTION

Staunton of the County of Auguste in the New Virginy States Mai the 28th 1779

Werthgeschätzte Eltern! Geschwister, Anverwandte und Freunde!

Da eine der günstigsten Gelegenheiten sich ereignet, um Briefe nach Europe zu senden, und das Schicksal mich so ausserordentlich glücklich macht, davon profitiren zu können, so muß ich Ihnen mit der größten Wahrheit sagen, daß ich Gottlob gesund bin; – ja, wie glücklich würde ich seyn, wenn ich hinsu setzen dürfte, daß ich allgemein vergnügt wäre. So bin ich es aber nicht, und Sie werden mir leicht glauben, warum! – Unser Schicksal ist noch nicht gebeßert – ein widriger Schluß hält uns noch in unserer Gefangenschaft, die zum Glück für uns, dennoch nicht so traurig, elend noch weniger aber gar unglücklich wäre, (was das Allgemeine betrifft) wie Sie vielleicht solche glauben. Man versagt uns zwar zum Theil etwas mehr Freyheit als wir bey Boston en general genommen hatten, und deren Beschaffenheit und Umstände ich Ihnen dazumal, und zwar im Monat Octobr 1778 gemeldet habe – allein – sehen Sie, auch hier schon wieder beunruhigt mich der Gedanke, ob Sie auch die 2 Briefe von Boston erhalten haben? bin ich auch hierzu nicht berechtiget? Denn wie mancher Chicane – wie manchen gefährlichen Umständen sind unsre Briefe bevor sie von freundschaftlichen antheilnehmenden Händen erbrochen werden, ausgesetzt. Erwarten Sie daher nicht meine Freunde! daß ich eine genaue Beschreibung unsers Marches von Boston bis nach Virginien Ihnen mitteilen werden. – Sie können sich alle Fatiguen eines Marches von 700 bis 740 Engl. Meilen (oder 150 deutsche Meilen) in einer so späten Jahreszeit als wir (neml. vom 10. Nov. 1778. bis d 16 Januar 1779) solchen haben zurück legen müßen, vorstellen. Erwägen Sie unsre Situation – und – denken Sie sich alle die traurigen Gegenden, durch die wir gekommen sind – die Passagen über weite Flüße, Berge, Wüsten und Wildnißen – und nehmen sie den, denen Einwohnern eignen und gegen uns hegenden natürlichen Widerwillen zu Hülffe, mit welchen sie uns offen mit Gewalt unter Dach und Fach bey der schrecklichsten Witterung aufnehmen mußten; – setzen Sie hierzu die schreckliche Theuerung in hiesigen Landen, wo wir alle Victualien 3 bis 4 mal so hoch bezahlen mußten; unsere elenden Umstände an Kleidunsstücke, Wäsche pp – (denn bey unserer Ankunft in Virginien hatten wir noch nichts, weder von unserer zurückgelaßenen Bagage in Canada, noch von unseren nachgeschickten Sachen aus unserm Vaterlande gesehen) vermehrten das Schreckliche unsers Schicksals. – Ich bin überzeugt, daß Sie uns alle herzlich bedauern werden und noch bedauern – und muß noch hinzu setzen, daß Sie sich aus denken sollen, wie wir so oft bey 3 bis 4 Fuß hohen Schnee unser Nachtlager im Walde und Wüstereyen haben aufschlagen müßen. – Mit einem Worte, denken Sie mich allen mir möglichen Fatiquen eines solchen Marches ausgesetzt – und – können Sie noch erwarten, daß es nicht dem gesetztesten Muthe gar oft um Trost und Beruhigung hat bange werden müßen. – Ich zweifle keinen Augenblick, daß Sie nicht für mich zittern werden, wenn Sie sich mir allen diesen benannten Gefährlichkeiten und Fatiquen exponirt imaginiren. – allein danken Sie Gott, daß Er mir Kraft und Gesundheit verliehen, alle diese Beschwerlichkeiten zu überstehen, – Muth, – männlichen Muth, gegeben, denen öftern Verführungen zu entgehen, und mitten im Trübsal, bey den Schrecklichsten Umständen, Pflichten der Ehre, – Pflichten der Liebe – Pflichten der Dankbarkeit gegen meine Theuerste Eltern und andren, eingedenk zu bleiben. Den 16ten Jan. a.c. kamen wir an dem Orte unserer Destination (7 Meilen von Charlottenville in der Caunty of Albermarle in Set [?] Virginien) – allein hier erwartete uns das Schrecklichste von allen. Unsere Barraquen waren nicht weiter fertig, als die 4 hölzerne Wände, die aber von Blöcken gemacht waren, zwischen denen 2 zur Noth ein Mensch aus und einkriechen konnte, – ein eben so elender hölzener Dach vermehrte unser Leiden, als der Schnee, der in unserer Barraque über 2 Fuß hoch lag, aufging. – Kein Camin – öffters keine Thür – und Fenster, waren nicht zu gedenken. – Wir mußten uns Feuer mitten in unseren Barraquen und nach 2 bis 3 Tage waren alle unsere Lumpen, und wir mitihm, gleichsam geräuchert. – Des nachts ließ uns der auf allen Seiten herrund ringende Wind und die heftigste Kälte keinen Augenblick schlafen, – und – wir lieffen in der That Gefahr, Hände und Füße zu verfrieren oder zu verbrennen. Noch ein abscheulicher Umstand war, daß man sich bey Niemanden beklagen konnte, denn jeder von uns, hatte ein nemliches Schicksal. Und ob Seiten der Americaner hieß es, man hätte unsere Ankunft nicht sobald erwarthet, man hätte nicht fertig werden können. Unser vom Marche ermüdete Leute fingen an, zu bauen, und zu beßern. – Jetzt sind die Barraquen in ziemlich guten Zustande. Ich war nicht länger auf solche als bis d. 4 Mart, als ich hieher commandirt wurde. Ich bin daher vor so vielen meiner unglücklichen Landsleute glücklich, daß ich 40 Engl. Meil, von unsern Barraquen in einem kleinen Städtchen mich befinde, – wo ich dem Empfang der Provisions für meinen General sowohl, als für andre hierwehernde Officers meines Corps annehmen, und [da?]rüber gehörigen Orts mich berechnen [muß?] [Diese?] Aide Commissair Stelle hat keine weitere Revenue für mich, als daß ich dem schrecklichen Schicksal entgangen bin, – auf denen Barraquen, die in einer öden Gegend aufgebauet sind, und woselbst unsre ganze Armee sich befindet, zu wohnen, und in einem solchen Getümmel so verschiedene Menschen, von eben so verschiedenen Grundsätzen nicht völlig dem Unglück unter zu liegen, das uns bis jetzt für den Dienst des Königs unthätig, für uns selbst in einer langweiligen, mißmüthigen, ja gar nachtheiligen Situation – für unsre Freunde in Europa gleichsam lebend todt, gefangen hält. Es hat ferner für mich den Nutzen auf der einen Seite, daß ich wenigstens nicht ganz vom Geräusch und Getümmel meiner unglücklichen Landesleute in meinem eignem Unglücke eingeschläfert und fühllos gemacht werde – da es auf der andern Seite mir in dem Umgange verschiedener gut denkenden Familien allhier überzeugt, daß nun all weise Vorsicht meiner noch nicht aus der Acht gelaßen, – ja, es beweiset mir daß man auf gewiße Weise mitten im Unglücke auch selbst glücklich seyn könne, wenn eigen Gewißensbiße und Vorwürfe böser Handlungen uns nicht dieses Glück verbittern. In diesem Monate habe ich bereits 5 Briefe von Ihnen M F erhalten. – Allein Traurig für mich – sie waren von 1776 u 1777 – Sie werden sich billig darüber erwundern, daß solche nicht eher erhalten habem Sie waren von England nach Canada gegangen, von woher ich sie mit unserer in Canada zurückgelaßenen Bagage, die jetzt angekommen ist, (neml. die neue Mondirung vor unser Regiment) erhalten habe. Die im Monat August 1777 an mich durch H. Krausen abgesandte 2 Packete mit Wäsche pp habe bis jetzt nicht empfangen – und man weiß auch nicht, wo alle diese Sachen von unser Corps hingekommen sind. Bedauren Sie mich daher beste Mutter (daß ich bey der gröste Nothwendigkeit solche noch entbehren muß. Wie sehr wünsche ich nicht acht Tage bey Ihnen zu seyn, um Ihnen vieles – sehr vieles zu erzählen – was ich theils meiner Feder nicht anvertrauen darf, und auch theils zu weitläufig wäre. Der Frau Fourier [Heinrich] Gerhard lassen sie doch sagen, daß ihr Mann sich wohl befinden – daß Er noch gestern mir einen Brief geschrieben – daß aber diese Gelegenheit einen Brief nach Europa senden zu können, so geschwind sich ereignet hat, daß ich meinen 40 Ml. abwesenden Freund Gerhard nicht solches vorher hätte kund thun um einen Brief von ihm an seine liebe Frau mit einliegen zu können. Wilhelm befindet sich ebenfalls wohl. Empfehlen Sie mich allen, die sich meiner erinnern – Ja! Meine threusten Freunde Vergeßet euren unglücklichen Freund nicht, deßen Herz für Euch die sehnl. Wünsche heget – deßen Augen jetzt, da der Raum des Papires ihm befiehlt, sich Euch und Eurer Freundschaft zu empfehlen – in bangen Thränen schliessen. – Lebt wohl! Lebt wohl! J. C. J. Dehn

Citation: Briefe von J.C.J. Dehn an seinen Bruder 1776-1782, H VI 6 Nr. 26 Blatt 29, Stadtarchiv Braunschweig.

One thought on “Inactive for the King’s Service. Virginia, 1779.”