In 1779, the Hessian chaplain Georg Christian Köster (Coester, Koester) pitied a local woman who had a child with a Hessian officer: “He had caused her downfall with a promise of marriage – nothing new in America, unfortunately.” When another soldier confessed to the chaplain that a woman in New York had become pregnant by him, Köster recorded in his “church book” that he “took an oath to be more careful in the future and swore to conduct himself as a proper soldier.” In 1780, the chaplain noted in response to the report of a local women that she had two children by a Hessian officer, “Therefore another pair of wretched boys and girls in the world! Therefore, take care and do not be fooled, By a man who promises to marry you!” Another entry in Köster’s record indicates that the Hessian Artillery Sergeant Johann Henrich Brethauer vowed he would marry Polly Tietzen of New York, the mother of his child, if he was given permission. If it was denied, he pledged to support the mother and child. Whether Brethauer honored this promise remains unknown.

Although the number of American women who became pregnant by a member of the German corps will never be known, scattered evidence, including records like those penned by Chaplain Köster, suggest that it was not a rare occurrence. It is important to note that, as in other wars, sexual assault was a common, albeit under-reported, atrocity during the Revolutionary War. Some of these pregnancies undoubtedly resulted from rape. However, the records also suggest that consensual, romantic relationships between German soldiers and local women were not unusual. The woman’s pregnancy motivated some of the men to seek permission for marriage from their commanding officer.

This was the case with the Braunschweiger Friedrich Ernst. During his stay in New York in 1781, he sought “consent” from his superior to marry a local woman identified only by her first name, Elisabeth. (As a general rule, surviving records that shed light on cases such as this reveal hardly anything about the woman. We usually do not even know her first name.) The two letters included with this post are also unusual for two other reasons. First, we have hardly any letters written by members of the German corps that served as servants or in similar (low-ranking) roles. Second, we have very few records about this subject that were penned by the men themselves. (To my knowledge, we do not have any records related to this issue written by a woman.)

Records indicate that a man named Friedrich Ernst was a servant of Johann August Milius, field chaplain of the Braunschweig Regiment von Riedesel. This servant was almost certainly the author of the two letters. Reverend Milius belonged to General Riedesel’s (military) family. He was one of the estimated 1800 Braunschweig soldiers that became American captives as a result of General John Burgoyne’s surrender at Saratoga in October 1777. Milius and his servants (he had two) remained with the Riedesel family during their time of captivity, first in Massachusetts and then in Virginia. They belonged to a group of around twenty officers and servants (as well as Friederike Riedesel and her three daughters) that traveled together from Virginia to New York in the fall of 1779 in order to be exchanged. They remained in the city for around 18 months. It was not until late spring 1781 that the general was able to make arrangements for their voyage to Canada.

It was probably his impending departure from New York that motivated Friedrich Ernst to request permission to marry Elisabeth, a local woman who had become pregnant by him. Although one of the letters does not name the recipient, it must have been Ernst’s immediate superior Chaplain Milius. We know that the recipient of the second letter was General Riedesel because it was addressed to him. Ernst hoped that Chaplain Milius would present his letter to the general directly. Clearly, he expected that the chaplain’s support for his request to marry Elisabeth would carry significant weight.

Although we know that Friedrich Ernst’s request was presented to General Riedesel (it is preserved in his papers), Riedesel’s response, if there was one, has not survived. Unfortunately, the records also do not reveal whether Friedrich accompanied the general on his voyage to Quebec in July 1781, either alone or in the company of Elisabeth. One hopes that they received permission to get married, and that they were able to live together as a family, whether in the United States, Canada, or Germany.

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

Letter One

Worthy Master,

I dare to present a request in writing, which I did not have sufficient courage to make verbally. For a long time, I have loved Elisabeth; for a long time, I have wished to be married to her; many times, I have wanted to risk telling Your Worthiness about it and to request consent for my marriage to said person; but every time fear has held me back. However, now my conscience and the tears of the unfortunate woman I have made unhappy (since she is pregnant by me) compel me to muster the courage and ask Your Worthiness not only for consent but also to request that you be so inclined to present the matter to the general. How happy I would be if I would receive consent through your advocacy; conversely, how unhappy would I be if I received a negative response from the general, and even more miserable would be the life of the woman that was abandoned by her siblings and relatives. I flatter myself with the sweet hope that Your Worthiness will approve of my intentions and will speak a word on my behalf to the general.

I am, Your Worthiness’s Most Obedient Servant Friedrich Ernst

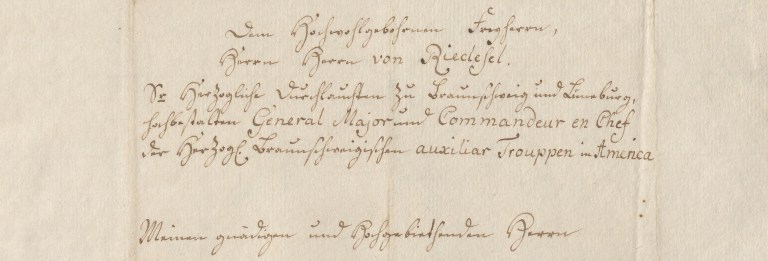

Letter two: recipient General Riedesel, dated Brooklyn, 24 May 1781

Most Highborn Baron,

Gracious and Most Honorable Major General!

I dare to present my most humble request directly to Your Excellency. The thought of having made an innocent woman unhappy (since Elisabeth is pregnant by me) weighs heavily on me. She had placed her complete trust in me, and now finds herself in a sad situation, having to leave her position by the end of this month without knowing where to turn for refuge. I feel it is my duty to beseech Your Excellency for your consent in this matter. How happy I will be, and even more so my now scorned and abandoned bride, who is shunned by her siblings and relatives, if Your Excellency would grant my humble request and give your consent. I will always serve faithfully and sincerely, and never forget my oath.

I remain, Your Most Highborn Grace, Your most humble and obedient servant, Friedrich Ernst

TRANSCRIPTION

Letter One

Wohlwürdiger Herr!

Ich wage demselben schriftlich eine Bitte vorzulegen, welches ich mündlich zu thun nicht Herz genug hatte. Schon lange liebe ich Elisabeth; schon lange habe ich gewünscht mit ihr verheyrathet zu seyn; vielmals habe ich es wagen wollen Erw. Wohlehrwürden davon zu sagen, und um die Einwilligung zu meiner Verheyrathung mit gedachter Person zu bitten; es hat mich aber jederzeit die Furchtsamkeit davon abgehalten. Nunmehro aber befehlen mir mein Gewißen, und die Thränen des von mir unglücklich gemachten Frauenzimmers, (indem sie von mir schwanger ist.) ein Herz zu fassen, und Erw. Wohlehrwürden nicht allein um die Einwilligung zu ersuchen, sondern auch daß dieselbe möchten die Gewogenheit haben und es dem Herrn General vortragen; wie glücklich würde ich mich schätzen, wenn ich durch deroselben Fürsprache den Consens erhielte; und dahingegen wie unglücklich würde ich seyn wenn ich von den Herrn General abschlächliche Antwort erhielte; und noch weit elender würde das Leben des von ihren Geschwister und Anverwandten verlaßenen Frauenzimmers seyn. Ich schmeichele mich mit der süßen Hoffnung, daß Erw. Wohlehrw. mein Vorhaben billigen werden; wie [illegible] daß Dieselben ein Wort zu meinen besten bey den Herrn G[eneral] sprechen werden.

Ich bin Erw. Wohlehrwürden Gehorsamster Knecht Friedrich Ernst

Letter two: recipient General Riedesel, dated Brooklyn, 24 May 1781

Hochwohlgebohrner Freyherr

Gnädiger und Hochgebiethender Herr General Major!

Ich wage es Erw. Hochwohlgebohrne Gnaden meine unterthänigste Bitte selbst vorzulegen. Die Vortsellung ein hilfloses Frauenzimmer unglücklich gemacht zu haben (indem Elisabeth von mir schwanger ist). Welches mir ihr ganzes Vertrauen geschenkt hatte; und die traurige Lage, in welcher sie sich anjetzo befindet, indem sie zu Ende dieses Monats ihre Herrschaft verlaßen muß, und keinen Zufluchts=Ort weiß, fordern es als Pflicht von mir Erw. Hochwohlgebohrne Gnaden ganz unterthänigst um den Consens zu bitten. Wie glücklich werde ich seyn, und noch weit glücklicher als ich wird sich meine anjetzo von ihren Geschwistern und Anverwandten verachtete und verlaßene Braut schätzen, wenn Hochdieselben meine unterthänigste Bitte erhören und mir den Consens bewilligen. Jederzeit will ich treu und redlich dienen und niemals meinen Eyd vergeßen.

Ich verbleibe Erw. Hochwohlgebohrne Gnaden ganz unterthänigst gehorsamster Knecht Friedrich Ernst

Citation: The two letters are included in “Schriftwechsel des Generalmajors Friedrich Adolf, Freiherrn von Riedesel…”, WO 237 N Nr. 61, ff. 83-84, Lower Saxony State Archives Wolfenbüttel.

Chaplain Köster’s church book is included in Bruce E. Burgoyne, ed., Hessian Chaplains: Their Diaries and Duties (2020).

Featured Image: François Boucher, A Pastoral Scene (‘L’Aimable Pastorale’) (1762), National Galleries Scotland.

One thought on “For a Long Time, I Have Loved Elisabeth. New York, 1781.”