I have found that documents that at first glance appear to be of limited historical significance to my research topic often help me broaden my understanding of an issue or place or time period in unexpected ways. The document included with this post serves as a good example.

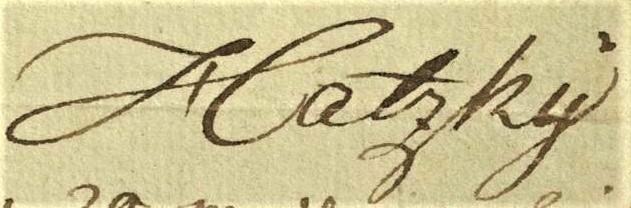

While conducting research at the Hessian state archives in Marburg, Germany, I came across a short letter signed by a man named Hatzky. He wrote it in New York in 1776. I made a note of this document mainly because it included an amusing reference to his inability to shave and, as a result, sporting a “beard like a rebel.” It is the only letter in the file that was penned by him.

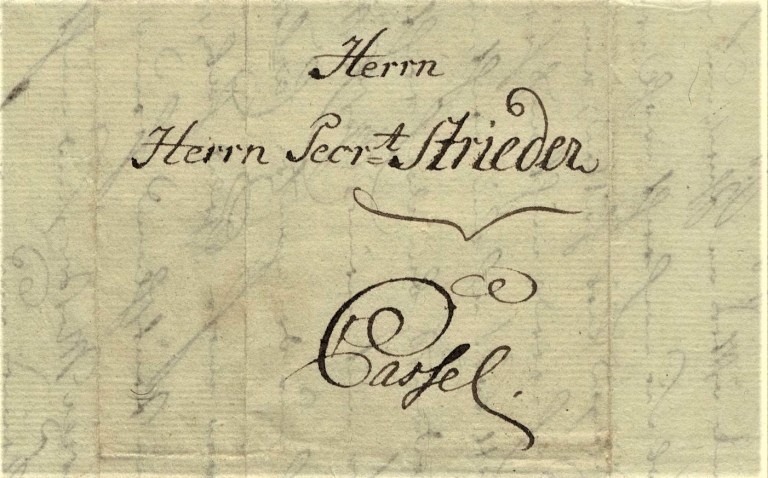

The letter is addressed to “Secrt. Strieder Cassel.” The title of the archival folder in which it is included offers more details. It is labeled “Privatbriefe aus dem amerikanischen Krieg, überwiegend an Friedrich Wilhelm Strieder [Private Letters from the American War, primarily to Friedrich Wilhelm Strieder].” Strieder (1739 – 1815) was a librarian, historian, and lexicographer based in Kassel. He is best known as the author and publisher of an 18-volume comprehensive history of Hessian scholars and writers, titled Grundlage zu einer hessischen Gelehrten und Schriftsteller Geschichte. Seit der Reformation bis auf gegenwärtige Zeiten, which he published between 1781 and 1806. But that does not explain why Hatzky may have corresponded with him.

I was curious about Hatzky and his connection to Strieder. Knowing this background would provide me with important context that would help me make sense of the document. Also, I do not recall previous encounters with Hatzky in my research on the Hessians. This made the letter only more intriguing to me. I was eager to learn more.

I started with the assumption that Hatzky was a member of the Hessian military, due to the fact that he sent the letter to someone in Kassel and also because he mentions an officer belonging to a Hessian regiment. However, a search in the extensive database of soldiers and other members of the Hessian corps (HETRINA) did not yield any results. Fortunately, the letter itself included a clue that offered an additional starting point for my search for information. Hatzky mentions that he had been engaged in business activities in “Carlshave.” This, I quickly determined, referred to Carlshaven (or Karlshaven, now called Bad Karlshafen), a port town on the river Weser roughly 25 miles north of Kassel.

After familiarizing myself with a basic overview of the town’s history, I searched online for any websites or publications that mentioned Hatzky and/or Strieder and/or Carlshaven/Karlshafen. It took a bit of digging, but my patience paid off: I came across an article from 1972 about a Hessian trading company that was based in Karlshafen and that was contracted to ship supplies to the Hessian corps in North America (Ottfried Dascher, “Die Handlungskompagnie zu Karlshafen (1771 – 1789): Ein Beitrag zum Verhältnis von Politik, Krieg und Wirtschaft im Spätmerkantilismus,” Hessisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte 22 (1972): 229-253). Naturally, this piqued my interest. In fact, I was pretty confident that there had to be some connection between this company and the letter. And sure enough, the article actually mentions Strieder and Hatzky. It turns out that both were employed by this company. Here is more:

In the 1770s, Strieder served as secretary to the Hessische Handlungskompagnie, or Hessian trading company. This stock company was founded in 1771 in Karlshafen for the express purpose of exporting products that were manufactured in Hessen. The landgrave himself was a major investor. From the start, the company struggled financially for a variety of reasons, including poor harvests that affected exports, limited access to shipping vessels, internal conflicts, and dubious business practices. The war in America offered a welcome opportunity to improve its fortunes.

After the conclusion of the Hessian-British subsidy treaty in early 1776, the company was awarded an exclusive contract to supply the troops from Hessen-Kassel with shirts and shoes (kleine Montierung). After the arrival of the Hessian troops in North America in the summer of 1776, the company maintained an outpost in New York. A detailed list of items purchased for Hessian field hospitals lists “Messrs. Hatzky & Co.” as a supplier of bedding, tea, wine and other goods. Over the course of the war, several shipments with recruits and supplies departed from Karlshafen for North America. Moreover, unbeknownst to the British and disguised as provisions for the troops and hospitals, the initial two shipments also included a significant volume of undeclared merchandise intended for the American market, including wine and spirits. However, due to a chronic shortage of ships (and most likely also corruption), the company soon failed in delivering goods (and profits) as promised and expected. By 1777, the company’s role in the American war was limited to that of sutler for the Hessian corps. It was no longer involved in shipping supplies and provisions from Hessen to North America.

The author of the letter was Karl Hatzky, a native of Greusen near Bendeleben in Thuringia. Hatzky had been employed by the company since 1772. He was one of three employees that were sent to New York from Kassel to represent the company, facilitate transactions, and help establish trade relations with the Americans. (I have not yet been able to identify the other two employees.) Based on the letter, we know that he was in New York in 1776. Moreover, we know from entries in Lieutenant Johann Karl Philip von Krafft’s journal that he was conducting business there in December 1781 and in February 1783 (“Journal of Lieutenant John Charles Philip von Krafft, of the Regiment von Bose, 1776-1784,” Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the Year 1882 (New York, 1883), pp. 155, 178). I would be surprised if he did not show up in other records. Now that I know his role in New York, I will keep an eye out for him. So far, I have not been able to determine his whereabouts after the return of the Hessian corps to Europe in 1783. The Hessian trading company seized operations in 1787/8. Unfortunately, its official business records have been lost.

In the letter, Hatzky explains that his business activities in New York are going quite well. However, the letter confirms the difficulties with getting supplies from Europe to North America. Business would be even better if he had all the “stuff” from Carlshaven with him in New York. In addition, Hatzky mentions Lieutenant Ludwig Wilhelm Henel of the von Trümbach Regiment (after 1778, von Bose). The archival file with Hatzky’s letter includes letters by Henel that were most likely addressed to Strieder. I have found no evidence for a formal link between Henel and the trading company. It is more likely that the two men were friends.

So, in the end, a short letter that caught my attention because of an amusing reference to shaving opened a window on interconnections between the Hessian economy, transatlantic trade, and the war in America.

And the short description included here is only the tip of the iceberg.

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

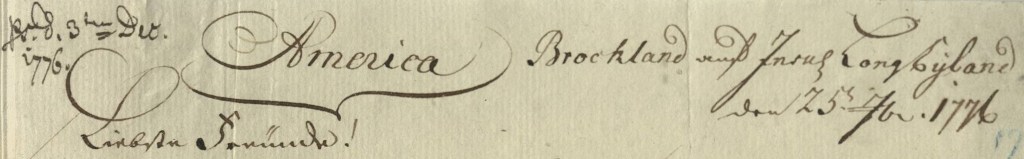

[notation in different hand] received Dec. 3, 1776

America Brockland [Brooklyn] on the Island Long Island, Sept. 25, 1776

Dearest Friends!

You may think that I have forgotten you; on the contrary, I often think of you and wish to know whether you remain well and whether you still love me a little bit. Regarding me, you can believe the latter, and I will not cease to love you very much. Thank God! I am quite well and despite the great annoyances, I am healthy and much more pleased with my business then I was in Carlshaven. Had I only all this stuff from Carlshaven, we would soon have more money than when the knight Hatzky had to ride all around Germany. I did not forget about your razors; I myself do not have one, and sometimes I have a beard like a rebel. Our old horse remains as impressive as before and it is healthy. It is serving us well. You will have to glean the rest from the Directions brief [official report?].

I am, until death, your faithful Hatzky

Lieutenant Henel has already written to me twice and asked about you. He is stationed on Staten Island, 20 miles from here.

TRANSCRIPTION

[In anderer Hand] [erhalten] 3ten Dec 1776

America Brockland [Brooklyn] auf Insel Long Eyland [Long Island], den 25ten Sept. 1776

Liebste Freunde!

Sie werden denke, ich habe Ihnen vergeßen, nicht weniger vielmehr denke öfters an Ihnen, und wünsche nur sogleich zu wißen, ob Sie noch recht wohl wären, und mich noch ein klein bißgen lieb hätten; von mir können sie letzters glauben, und ich werde nicht aufhören Sie recht sehr zu lieben: Gott lob! ich bin recht wohl, und bei den großen Verdruß, bin doch recht gesund und wei[t] vergnügter mit meinen Geschäfften als zu Carlshave. Hätte ich nur das gantze Carlsh: Cram hier, bald wolte wir mehr Geld habe, als da der Ritter Hatzky in Teutschland herum reute mußte. Ihre Rasier Meßer sind nicht vergeßen: ich habe selbst keines, und manchmahl Ein Barth wie ein Rebelle. unser altes Pferdt hat noch seinen Stoltz wie vorhür, und recht gesund. er thut uns gute dienste; das übrige müssen Sie aus dem Directions brf [Brief?] ersehen. ich bin bis in todt Dere treuer Hatzky

Hr. Lt Henel hat schon 2 mahl an mich geschrieben, und nach Ihne gefraget, er steht auf Staaten Insel, 20 Meilen von hier

Citation: Hatzky to Strieder, New York, September 25, 1776, in “Privatbriefe aus dem amerikanischen Krieg, überwiegend an Friedrich Wilhelm Strieder, 1776-1779”, Hessian State Archives Marburg, HStAM Fonds 4 h No 3787, f. 9.

For the purchases made by the Hessian field hospital in New York, see HStAM 4h Nr. 4156, Hessian State Archives Marburg.

As mentioned above, a key source of information about the trading company is Ottfried Dascher, “Die Handlungskompagnie zu Karlshafen (1771 – 1789): Ein Beitrag zum Verhältnis von Politik, Krieg und Wirtschaft im Spätmerkantilismus,” Hessisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte 22 (1972): 229-253.

Featured Image: Detail from illustration in Jean-Jacques Perret, La Pogonotomie, ou L’art d’apprendre à se raser soi-même … (Paris, 1769). Digitized copy accessed here.

I have often stated that you have to think and act like a detective to figure out the context behind statements by participants in the past. Quite interesting story about a beard.

LikeLike