The depreciation of paper money was a major problem during the American Revolution. Hard currency was scarce. Comments about the disastrous financial situation of the rebellious colonies appear frequently in letters, diaries, and similar accounts penned by members of the German corps. Some observers thought that the crisis would sooner or later force the rebels to give up their struggle. Other believed that it had the opposite effect: they thought that it compelled the people to stand united and continue the fight in order to avoid complete ruin. The author of the document featured in this post held the latter view.

In July 1777, more than 15,000 British and German troops along with officers, staff and servants, boarded transports at Staten Island that would take them to Philadelphia. They were under the command of General William Howe. In August, the fleet landed in Maryland, and from there the army made its way north toward Philadelphia. On September 26, they marched into the city. They would remain until June 1778, when the British decided to evacuate the city and withdraw the troops to New York.

The document included with this post consists of an excerpt from a six-page letter probably written by the Hessian Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Wilhelm von Wurmb. Wurmb belonged to Howe’s army, and he wrote the letter in Philadelphia in February 1778.

The recipient of the letter was Friedrich Christian Arnold, Baron von Jungkenn (1732-1806). In 1778, Baron von Jungkenn was a major general and Lord High Chamberlain at the Hessian court in Kassel. Over the course of the Revolutionary War, he actively corresponded with a number of Hessian officers in North America, including Johann Friedrich von Cochenhausen, Johann August von Loose, Karl Wilhelm von Hachenberg, Friedrich Wilhelm von Lossberg, Johann Ewald, and Karl Leopold Baurmeister, to name only a few.

When Colonel Wurmb wrote his letter to his friend in early 1778, the Continental Army under General George Washington was encamped at Valley Forge. Roughly 12,000 men and several hundred women and children spent the winter months only a day’s march away from British-held Philadelphia. Although this was not the coldest winter during the revolutionary war, bad weather, a shortage of provisions and supplies, and outbreaks of disease rendered living conditions deplorable.

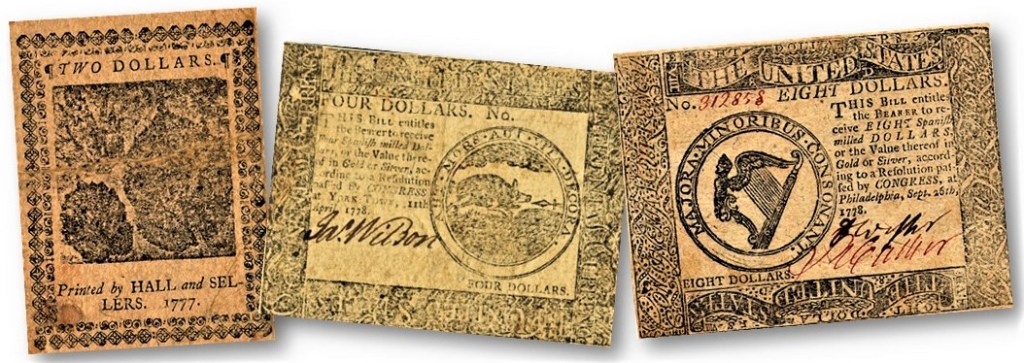

Colonel Wurmb mentions in the letter that Washington and his army were in need of clothing and provisions. In addition, he is suggesting that inflation was a major reason for these problems. He was right. In 1775, the Continental Congress and the individual colonies had begun to issue paper money. In order to pay for expenses associated with waging the war, they printed more and more of it. The result was hyperinflation. Prices spiked while the bills’ values depreciated rapidly. Counterfeiting made matters worse. Not surprisingly, confidence in paper money plummeted. At the same time, specie (silver and gold coins) was in short supply.

Colonel Wurmb was not only explaining that the depreciation of paper money was causing hardship. He was also speculating that the “damned paper” was uniting the people in their dependency on Congress and opposition to ending the war. They believed, he explained, that peace would make their lives even more miserable. The Hessian officer was convinced that the Congress was benefiting from the issuance (and depreciation) of paper money both politically and financially.

Letter from Friedrich Wilhelm von Wurmb to Friedrich Christian Arnold, Baron von Jungkenn

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

Philadelphia, February 7, 1778

[…] You know that on December 30, we moved into winter quarters in Philadelphia, where so far we remain very quietly and well. I am very pleased with them [the quarters] in regards to the regiment. General Washington [“Wasinden”], who is located with his army four to five hours from here near Valley Forge, is not causing us any inconveniences, and it seems as though he is very glad that we are letting him go. According to every deserter, of which many are coming to us, they are lacking every kind of clothing, as well as salt, rum or liquor, wine. General Washington [“Watzindon”] is not drinking anything but rum and water at his table. Nevertheless, I do not think that we will be getting peace this year, and I believe that they will not make peace as long as Congress can raise 1,000 men. The Congress could have had a more favorable valuation than the one with paper money. In the initial rage and fervor at the beginning of the rebellion, all of the wealthiest and distinguished people and all the others handed over their hard cash and took paper money in its stead. This cash was sent to France and the West Indies to acquire war supplies. Now the inhabitants have nothing but paper money. If there were peace tomorrow, a man who has 50,000 pounds would not have enough to buy a piece of bread. Therefore, everybody is saying that they do not want to make peace because they would have to starve and go begging, and this damned paper creates this great unity among them. Everybody is looking to the Congress for that reason, and if they had to do it again, they would not do it. In the meantime, Congress has the property [cash] and the others have the paper money. […]

TRANSCRIPTION

Philadelphia, den 7ten Feb 1778

[…] Es ist Dier bekannt dass wier Den 30ten Decbr die Winter Quartiere in Philatelphia bezogen haben, wo wier noch bis hierhin ganz ruhig und gudh liegen, ich bin sehr wohl in Ansehung des regiments dieserwegen zu frieden, Der General Wasinden welcher mit seiner arme bey Wallen Fort [Valley Forge] 4 bis 5 Stunden von hier stehet, incomodiert unß nicht, und scheint als ob er sehr froh ist, daß wier ihn gehen laßen, seine arme nach aussage aller Deserteurs, welche sehr häufig kommen, sagen auß, daß es an allen ardhen von Kleidungsstücken fehlet, und an Salz, rum, oder Brandwein, Wein, der General Watzindon trinkt nichts als rum und Wasser an seiner Taffel, dem ohngeachdet glaube ich nicht dass wier dieses Jahr Friede bekommen, und ich glaube so lange der Concres noch 1000 Man aufbringen kan sie keinen Frieden machen, Der Concres hätte einmahlen einen Gescheideren Anschlag haben können als denjenigen mit dem Papier Gelde, alle die reichsten und Vornehmensten, und alle übrige, gaben bey dem Anfange dieser rebellion in der ersten Wudh und Hitze, Ihr pahres Geld her, und nahmen an dessen Stelle Papier, dieses Geld wurde nach Franckreich, und Westjndigen geschickt, um Kriegs Betürffnisse Davor anzuschaffen, nun mehro haben die Einwohner nichts als Papier Geld. Wen nun ein Mann der 50M lb reich ist, und morgen Friede würd, so hat er nicht so viel daß er kann ein stück Brodt kauffen mithin saget jederman Wier wollen kein Frieden Machen, denn Wier müssen sonst Bettelen und hungeren, und dieses Vertamte Papier macht eben die grose Einigkeit unter sich, es schild jeder man auf den Concres dieses wegen, und wen sie es noch einmahl zu dhun hätten würden sie es nicht dhun, unterdessen der Concres hat dass xahon [?] und die anderen dass Papiergeld. […]

Featured Image: 50 Dollar note. Accessed at https://coins.nd.edu/ColCurrency/CurrencyText/CC-09-26-78b.html

Citation: Wurmb to Jungkenn, February 7, 1778, in Freiherr von Jungkenn papers, 1775-1784, Box 1 Folder 63, University of Michigan Clements Library. A finding aid to the collection is available online.

I’m amazed at the German written by von Wurmb. While it expresses sophisticated thoughts there’s a lot of variation in spelling and capitalization and it’s written to a high official of the government.

Yes, the American economy of that time was struggling, a good reason to fight.

It’s also important to remember that America was still divided on support for the war, some were loyal to Great Britain, and some were neutral in addition to those who supported the war. Division is a thread through American history.

LikeLike